It was all meant to be so different after the Second World War. The men and women who defeated fascism were to be honoured with new homes, a National Health Service and a welfare state providing support from cradle to grave.

But the neds of Dundee had other ideas. While they could not lay a mitt on the NHS or the welfare state, they did their best to crush the dream of new homes in the broad uplands beyond the city’s old boundaries.

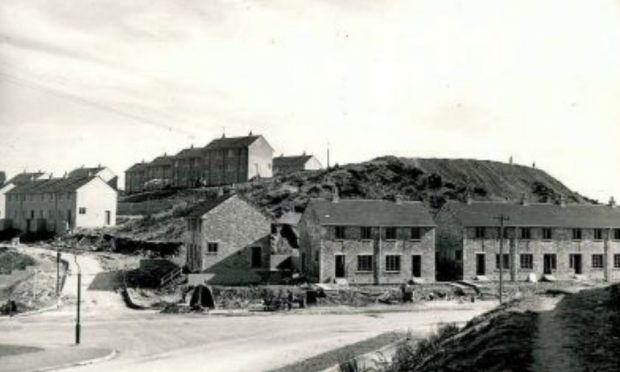

As millions of pounds were pumped into new schemes at Kirkton and Dryburgh to replace slums, vandals worked hard to slow the progress of the builders.

City architect Mr J McLellan Brown admitted it was almost impossible to keep pace with the damage. After a visit to the second phase of the Kirkton scheme, he reported to Dundee Corporation that in just six blocks, nearly 60 clay drain connections were smashed, drain covers stolen, water pipes torn from the ground and sleeper joists and doors stolen.

The tiled roofs on three blocks looked like they had been hit by an explosion.

Holes had been knocked in ceilings and plasterwork, light switches were broken and had their wiring ripped out.

In Ambleside Terrace, in just 14 houses, 380 panes of glass were smashed.

Across in Dryburgh, vandals smashed 1,300 windows in a short stretch, smashed baths and stole, 40 yards of asbestos piping and 70 yards of iron piping before setting a concrete mixer on fire.

There were demands in The Courier’s letters column for a detachment of police or watchmen to be on site at all times.

Martin McMillan, 21 Glenprosen Drive, even called for a citizens’ army to defeat the vandals. He finished his letter of August 1950 by calling for the birch to be used on the neds.

Although it was largely a post-war creation, planning of Kirkton began in 1939 when the corporation invited tenders for the first phase.

Once Kirkton was occupied, councillors turned their attention to Douglas and Angus, issuing tenders worth £919,601 in March 1952. A three-bedroom apartment would cost £1,541 to build.