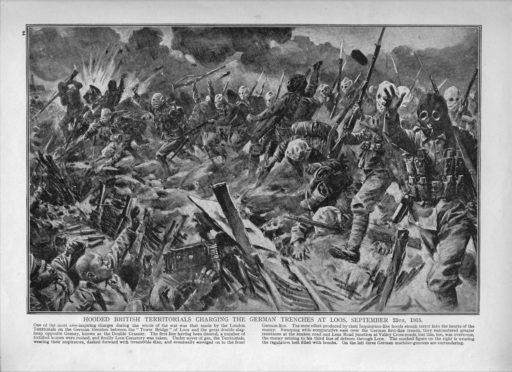

On the morning of September 25 1915, long lines of khaki-clad British infantry advanced on heavily defended German positions in and around Loos, a small coalmining town in the heart of the industrial area of north-east France, says Dr Derek Patrick, University of St Andrews.

The attack had been preceded by an artillery bombardment that began on September 21. Chlorine gas and smoke was discharged at 5.50am, to compensate for what Sir Douglas Haig, Commander First Army, whose men would execute the advance, considered insufficient artillery support.

This was the first time the British would use gas as a weapon in the First World War. Loos was not a battle of Britain’s choosing. It was fought in support of larger French operations in Artois and Champagne. Politically, it was important that Britain was seen to be playing her part in support of her French ally.

The British Expeditionary Force would attack on a wide front extending from the La Bassée Canal to Loos. From the outset Haig had serious reservations about the proposed offensive. The German defences overlooked the British front line along its full length, and the ground between was open, devoid of cover, and studded with industrial buildings, and mine workings, which presented a difficult challenge to Haig’s First Army.

The advantage as regards the Loos battlefield was clearly with the German defenders. The advance would be made by six divisions, with three in reserve, supported by more than 100 heavy guns. The attacking force included three regular, one territorial force and two new army divisions – 9th and 15th (Scottish) Divisions. Thirty-six battalions, half the number that participated in the opening stages of the battle, were from Scottish regiments. In total, more than 30,000 Scots would take part, most serving in the two Kitchener New Army divisions, representing communities across Scotland.

The ranks of these battalions, representative of each of the 10 Scottish infantry regiments, were not exclusively “Scottish”. The kilt and Scotland’s martial traditions had broad appeal. But the disproportionate number of Scots who went over the top at 6.30am on September 25 1915 ensured Loos would be remembered as a Scottish battle. Despite impressive gains on the opening day, Loos was a missed opportunity. The reserve divisions who could have exploited the gains of the 9th and 15th Divisions were too far from the battle area.

Consequently, the achievements of September 25 were the high water mark for the British Army at Loos, culminating in Sir John French’s removal as commander-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force in December 1915, and replacement with Sir Douglas Haig. The battle would continue until October 13 1915, but any hopes for a major breakthrough had long since evaporated. Scotland’s contribution to the “great advance” is clearly reflected in the extensive casualty returns. Official sources record some 470 officer and 15,000 other rank casualties on the first day of the battle, although it has been suggested the figure could have been higher. Because Scottish divisions were making the main attacks, they suffered particularly heavily.

The 4th Black Watch, “Dundee’s Own”, had gone into action with 21 officers and about 450 men. Casualties amounted to 20 officers and some 240 other ranks – killed, wounded and missing. The war exacted a heavy toll on the city. By the Armistice some 63% of eligible men had served with the colours, and more than 4,000 made the ultimate sacrifice. This contributed to one of the highest casualty rates in Scotland. Dundee’s experience of the war became synonymous with the fate of its battalion at Loos and each year, the bronze brazier on the Law is lit to commemorate the city’s losses.

A soldier’s story

James Ramsay of Kirkcaldy has written an account of his father’s lucky escape at the Battle of Loos: “My father, Private Robert Ramsay, was in The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) and was 20 at the time. The information I have is a bit sparse, but what I know is that he fought at the Battle of Loos.

“They were being bombarded with shells. They heard them coming over, and were instructed to get behind a hay stack but my father just fell to the ground. The hay stack was demolished and everyone was killed – apart from my father. He was hit in the back with a piece of shrapnel, wounding him, but he was very lucky – he had his rations on his back with biscuits and tinned bully beef, and he reckoned the tin helped to stop the impact of the shrapnel and probably saved his life.

“He crawled for quite a distance with blood filling his boots. He eventually came to a small house. He asked where the nearby medical centre was and they took him there. It was like a conveyer belt with all the wounded getting treatment.

“He was then taken to the coast and then on to England where he was put on a train for Scotland. He actually travelled in the luggage rack for the journey to Stobhill Hospital in Glasgow for treatment. He had a hole in his back the size of your fist.

“He was then moved to Chatsworth Mansion House near Derby for convalescence.

“Once he was fit, he became a Redcap. After that he worked on various farms in the East Neuk of Fife. He lived till he was 95 and today his family all owe their lives to that tin of bully beef.”

Courier reader Bill Naismith has sent in the notification of his grandfather Thomas Naismith’s, death which occurred during the 4th Battalion’s (Dundee’s Own) action during the Battle of Loos, September 25, 1915 at Moulin Pietre near Neuve Chapelle, north of La Bassee canal.

“A report of the last sighting of him in enemy trenches was published in The Courier in an article not long after the battle. He left a widow and six children.”

Buy your copy

First World War – The Scottish Soldier’s Story, is a 150-page compilation of The Courier’s commemorative special First World supplements 1914-1918.

£11.99 with free p&p, available from www.dcthomsonshop.co.uk or call 0800 318 846 (Freephone), quoting CSOST, lines open Mon-Fri 8am-6pm, Sat 9am-5pm.

Also available from the DC Thomson Shop, Albert Square, Dundee DD1 1DD