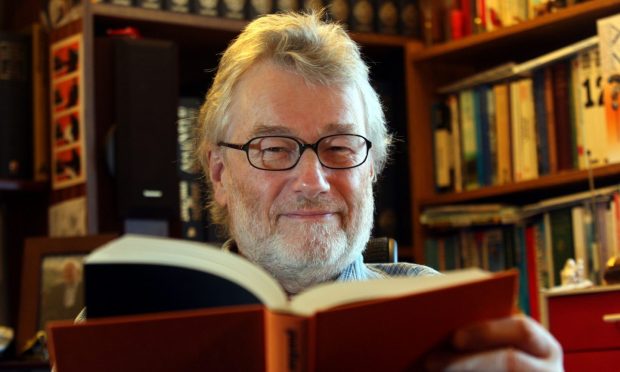

Michael Alexander visits the Ancient Egypt Rediscovered exhibition which has just opened in a new, permanent gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.

There’s no such thing as bad publicity, goes the old saying.

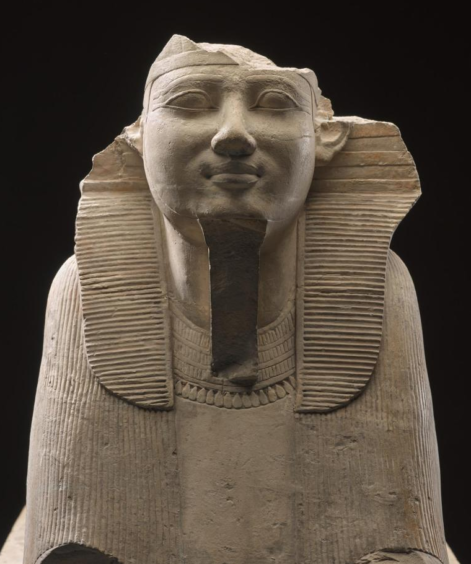

But when staff at the National Museum of Scotland (NMS) were putting the finishing touches to the new Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery which opened on February 8 as part of a 15-year, £80 million redevelopment of the iconic Edinburgh museum, they did not expect to be caught up in a row about whether it has permission to exhibit a 4,500-year-old casing stone from an Egyptian pyramid.

When it was announced last month that the block of limestone from the Great Pyramid of Giza was to go on public display for the first time as a centre piece of the permanent exhibition, Egypt’s Antiquities Repatriation Department cast doubt over its authenticity and documentation.

It asked for a certificate of possession and export documents and said measures would be taken to repatriate any artefacts found to have been illegally smuggled out of Egypt.

However, the NMS has insisted that a British engineer was given permission to take the stone in 1872 and, after reviewing all the documentary evidence it holds, the museum is confident that they have legal title to the stone and that the appropriate permissions and documentation were obtained in line with common practice at the time.

“It was found by Waynman Dixon in 1872,” a spokeswoman for NMS told The Courier.

“He uncovered it amongst a rubble heap resulting from road building works which had been undertaken by the Egyptian Government in 1869.

“Waynman Dixon was working on behalf of the Astronomer Royal of Scotland, Charles Piazzi Smyth.

“In 1865 Piazzi Smyth had initiated a programme of research including the first largely accurate survey of the Great Pyramid.

“In doing so, he had the official permission of the Viceroy of Egypt and the assistance of the Egyptian Antiquities Service.

“The stone was brought to the UK by Waynman Dixon in 1872 and transported to Charles Piazzi Smyth in Edinburgh.

“After reviewing all the documentary evidence we hold, we are confident that we have legal title to the stone and the appropriate permissions and documentation were obtained in line with common practice at the time.”

Margaret Maitland, senior curator of the Ancient Mediterranean at NMS for six years, said she was “certainly surprised” to hear of the “unexpected” controversy.

However, she too expressed confidence that the museum had legal title to the object and emphasised it was just one of a number of “amazing” objects going into the gallery – the opening of which coincides with the 200th anniversary of the first ancient Egyptian objects entering the NMS collections.

One of three new galleries that opened on February 8 alongside Exploring East Asia and the Art of Ceramics, the Egyptian gallery on level five, explores how the ancient culture evolved across more than 4,000 years of history.

Made possible through the support of The National Lottery with the Heritage Lottery Fund as well as other major trusts, foundations and individual donors, it spotlights the remarkable stories of individual objects and the people who made, owned, and used them, as well as those who eventually rediscovered them.

“We had a permanent Ancient Egypt gallery in the past,” said Margaret.

“That closed in September 2014 as part of the major redevelopment of the entire museum.

“This is our new permanent Ancient Egyptian Gallery bringing the collection back on display.

“It’s the biggest redesign of that gallery for quite some time. The majority was in the previous gallery but around 40% of the objects haven’t been on display in generations. That’s really exciting.”

The gallery is divided into four sections: the rise of ancient Egypt when people first thrived in the Nile valley; rebellion and renaissance – when the power of early kings declined and shifted to local rulers; a golden age – Egypt’s empire building period, and the empire strikes back – when foreign rulers dominated and left their mark on Egyptian culture.

Margaret explained that most of the gallery is presented chronologically, conveying the sheer breadth of Egyptian history and examining how its culture changed over time, including through interactions with the wider Mediterranean world.

Further sections compare burials in different periods and look at how monument building shifted from pyramids to temples.

The stories of specific individuals are told, exploring what their lives were like at a particular time and place.

These include a girl named Tairtsekher who lived in the village of the workmen who built the tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

“The first objects that came to the collection in 1819, and originally went to the university, are a coffin, a mummy board and a mummified man,” she said.

“But the majority of our collection dates much later than that.

“We have quite a lot of objects that came from archaeological excavations. Indeed, a large proportion of the early beginnings of our collection came through (Wick-born antiquarian and Egyptologist) Alexander Henry Rhind who was really the first experienced archaeologist to excavate in Egypt.

“He went out in the mid-1850s and applied for permission to excavate and bring objects back for the national collection. He pioneered techniques excavating brochs in the north of Scotland.

“He was then able to do really amazing work in Egypt because of his experience in that. His collection is the main feature in the gallery.”

Margaret said it’s “hard to choose” her favourite from the objects on display.

However, she said there were some “really amazing objects for people whatever their interest”.

These range from a “really tiny exquisite gold catfish pendant” which is being displayed up close to the glass for detailed examination, to a cosmetics box which is one of the finest examples of decorative woodwork to survive from ancient Egypt.

There’s also an “amazing unique” double coffin made for two half-brothers who lived in or near the ancient Egyptian capital of Thebes – the only coffin to survive from Egypt made for two people.

While personalised funerary artefacts reveal that one of the deceased was three years and three months old, little else is known about the brothers other than they were clearly of a wealthy family and the unique style of coffin has allowed archaeologists to connect it with other coffins of the same era or even to others made by the same craftsman.

“It’s really extraordinary because it’s still fully within the Egyptian tradition of mummification and all of the sort of symbolism that goes around that,” said Margaret.

“Typically Egyptian coffins of the era were painted with an image of the sky goddess to protect the deceased.

“But this one, because it had two people in the same coffin, there are two sky goddesses depicted protecting each of the children.

“I think it will surprise people the style of art as well because it’s a Roman era coffin – it’s got quite a more classical style of representation of the figures.”

Of course, many people associate Ancient Egypt with ancient curses.

The curse of the pharaohs is an alleged curse believed by some to be cast upon any person who disturbs the mummy of an Ancient Egyptian person, especially a pharaoh.

However, despite the legend of Tutankhamun, Margaret said there’s actually little evidence to back curses up – and where threats were made, they tended to be less dramatic.

“We actually have popular mythologizing of curses – they tend to be blown out of proportion compared with how the ancient Egyptians would have thought about it,” she said.

“The amount of evidence that we have of so-called curses – there isn’t actually any officially written in ancient Egyptian times on Tutankhamun’s tomb.

“But we do actually have a rare example of a warning message from an ancient Egyptian tomb where the inscription is quite sort of vaguely worded.

“It suggests that whoever reads the message shouldn’t take anything out of the tomb – not even a pebble – less the gods reproach them very very gravely.

“There aren’t any sort of gruesome threats in there.

“But we do actually have in the collection an unusual example of this.

“It was much more common for such warnings to actually threaten taking any sort of transgressors to court in the afterlife to face a tribunal of gods – which is maybe a bit less than what people imagine!”

*The new Ancient Egypt, East Asia and Art of Ceramics galleries are open free at the National Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh now.