While cities such as Dundee struggle to deal with drug-deaths and addiction, a similar sized seaside town in England is already making a difference through a landmark project.

But the scheme credited with turning lives around in Blackpool is not being tested in Scotland.

Project Adder aims to address addiction and tackle supply in the hardest hit communities across England and Wales.

The Scottish Government was invited to join, but declined.

Last week, the SNP unveiled its own approach to tackle the problem with plans for the country’s first drug consumption room.

So was this a missed opportunity?

In the week new estimates revealed a 7% rise in drug deaths in Scotland for the first six months of 2023, we travelled to the Lancashire resort to see first hand how the scheme rejected by ministers at Holyrood is saving lives and transforming approaches to drug crime.

Centres of drug abuse

We chose to go to Blackpool because, with a population of 141,000, it is similar in size to Dundee, at 148,000. Both communities struggle with an unenviable reputation as centres of drug abuse.

When the scheme was introduced, Blackpool had the highest rate of drug-related deaths in England and Wales with a percentage almost five times higher than the average for England.

Meanwhile Dundee for years held an even worse title – the city with the highest drug death rate in Europe.

How Blackpool identified the problem

Blackpool’s problems are with heroin and crack cocaine. But this is largely hidden from tourists by the use of dispersal orders, which force addicts and dealers away from the beach front area.

Dealers from neighbouring cities see the resort as a perfect target market thanks to its high levels of deprivation.

Where once its rows of B&Bs were full of families enjoying a seaside break, the changing face of tourism has altered that.

Instead, many have been converted into multiple occupancy accommodation for vulnerable and homeless people from other towns and cities.

The result was a town with more than 2,000 opiate and crack addicts.

While we are still police officers, we are trying to sign-post those individuals who we consider to be addicts towards treatment.

– Detective Sergeant Andrew Clitheroe.

In Blackpool, a team of six police officers works with five enhanced drug outreach workers, an outreach nurse as well as a special Lived Experience Team – each one with experiences of drugs, prison or homelessness.

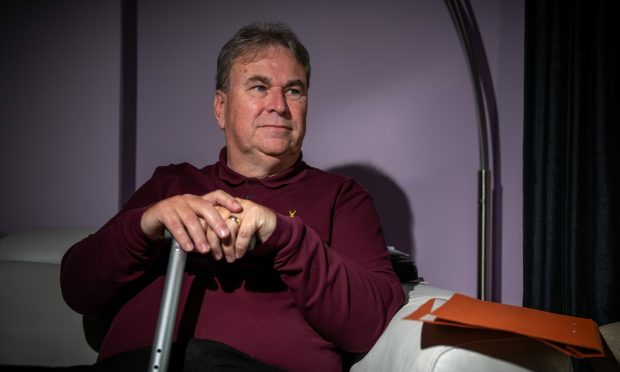

Detective Sergeant Andrew Clitheroe is part of that team, which has already disrupted at least seven major lines of drugs being transported into Blackpool.

DS Clitheroe said: “Primarily when police officers deal with addicts, it’s shoplifters and people committing those kinds of offences, and it’s from a prosecution perspective.

“Project Adder is about having a shift in approach.

“While we are still police officers, we are trying to sign-post those individuals who we consider to be addicts towards treatment and help and assistance, to move them away from coming into the criminal justice system.”

Greatest risk

He tells of being sent out on warrants to the same address six or seven times in the space of 18 months and wants to break the cycle of low-level criminals motivated by scoring drugs being prosecuted and then re-offending.

“With drug deaths, if you spoke to the people who work in the treatment centres and police officers, they can all anecdotally tell you the five or 10 people that are at the greatest risk,” he added.

“They’re the ones constantly coming into contact with police services or coming into hospital.”

The UK Government claims Adder is a success, with nearly 5,000 people helped to join a treatment programme, 25,000 criminals arrests, and seizures of £10 million in cash in its first two years.

In Blackpool, local police made 197 arrests and brought forward 177 charges as part of the scheme but perhaps more importantly have produced 746 intelligence reports.

Adder has resulted in 9,208 out-of-court disposal orders issued for drug possession offences, guiding vulnerable people exploited by gangs away from the criminal justice system and towards treatment.

That has been made possible by a shift in approach away from locking up runners who are often users themselves and being used by criminal gangs as they try to support a habit.

‘Cuckooing’

Clitheroe’s colleague, DI Kathryn Riley, gave a recent example of a vulnerable woman whose home was being used by dealers as a base – so called “cuckooing”.

The woman turned up at one of the charities linked to Project Adder and said she was too scared to go home because there were a number of people using the property.

Because of the partnership between the police and agencies, officers were able to deploy a team and arrested five individuals – including two who were already wanted.

But Riley cites what happened next as the real power of Adder.

The vulnerable woman left her home to avoid being exploited but because she was voluntary homeless, this meant she was not eligible to get a new flat.

Police were then able to show logs of their contact with her and arrange for the woman to be given a new flat in another city away from the groups who had been exploiting her.

Riley said: “It’s about a collaborative approach to remove people from situations, from risk and harm which ultimately increases their drug use and chances of non-fatal overdoses and drug deaths.”

Project Adder has also linked police with people who have experience of drugs and chaotic lifestyles.

Nicola Plumb spent 20 years accessing services before turning her life around.

She now leads the Lived Experience Team in Blackpool, a group of 21 staff who use their backgrounds to engage with people at the highest risk.

“It’s about meeting people where they’re at. Being kind and being human,” she said.

“We have an amazing relationship with the police now and we never expected that.

“I hope this will be a permanent change.

“When you have everyone working together to really give that wrap around support, that gives people the best possible chance of getting clean and turning things around.”

Conversation