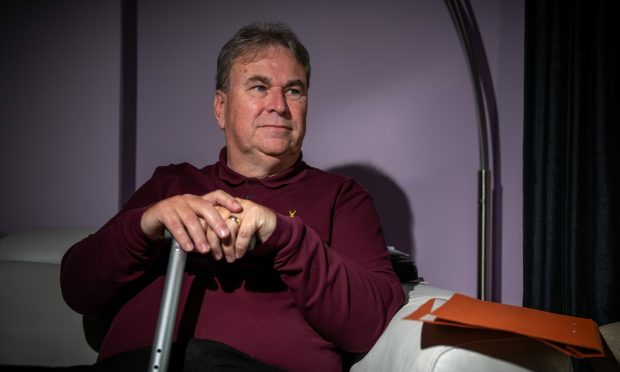

There are moments, Derek Mackay admitted recently, when he doubts whether he is really good enough to do his job.

The 42-year-old, who will this week deliver his fourth Budget since taking on the challenging post of finance secretary, highlighted his struggle with “impostor syndrome” in an interview with Holyrood Magazine last month.

Given his rapid rise to prominence, it might have been more surprising if Mr Mackay had said he had never questioned himself over the years.

After all, he was elected as a councillor in Renfrewshire at just 21, in 1999, served as council leader from 2007, including during the global economic collapse, and he became a government minister at 34, just a few months after his election to Holyrood.

In fact, his status is now such that Mr Mackay is widely considered to be one of the leading contenders to be the next first minister of Scotland, when the tenure of his friend and ally, Nicola Sturgeon, comes to an end.

But it was unclear from his interview whether Mr Mackay genuinely was unsure about his own ability.

He may simply have made the remark to tee himself up for a joke at the expense of his Conservative counterparts at the Treasury.

In the same breath, Mr Mackay said that while he occasionally felt like an imposter, he was reminded that he was “perfectly up to the job” every time he met his “imperial masters” at Westminster.

I sometimes have impostor syndrome and I don’t think it’s a bad thing to admit that there are times when I don’t think I’m good enough to do the job, (but) I have to say, having met my so called imperial masters, I am feeling perfectly apt and perfectly up to the job.”

The jibe, which was branded “immature” by the Tories in the row that duly followed about his use of the phrase “imperial masters”, was typical of Mr Mackay.

Self-effacing but simultaneously supremely self-confident, all while using language calculated to create headlines, infuriate opponents and delight SNP supporters.

It is one of the reasons he is held in such high regard by his supporters, of which there are many, despite Mr Mackay not necessarily being the most charismatic politician in his party or parliament, and arguably not having the public profile that might be expected of the second most powerful figure in the Scottish Government.

He is also well-liked among the grass-roots because of the obstacles he has overcome in his life, and because he was and is one of their number.

He knows everyone in the party, gets on with everyone and works hard.”

Mr Mackay was raised on a council estate in Renfrew, and told the Paisley Daily Express in 2016 that his family sought refuge in a homeless shelter for several months during his early teenage years.

He joined the SNP at 16 and was national convener of the Young Scots for Independence, becoming the first member of his family to go to university, before dropping out to stand for the council in 1999.

At that time, as has since been recalled in a Herald on Sunday profile, the young activist was far from the moderate he is now perceived to be.

During the late 1990s, around the time the first Scottish Parliament was opening, Mr Mackay was in the “fundamentalist” camp of the SNP, which wanted to focus firmly on independence, rather than than the “gradualists”, including Ms Sturgeon and Alex Salmond, who hoped to use devolution as a stepping stone.

As it turned out, Mr Mackay was destined to play a prominent role in the parliament he was once sceptical about, making the transition from local to national government almost nine years ago.

It was Mr Salmond who appointed him to his first ministerial post in December 2011, seven months after Mr Mackay arrived in Holyrood, giving him the local government and planning job as part of a mini-reshuffle.

In his personal life, a significant change followed in 2013 when the married father came out as gay and separated from his wife.

Influence enhanced

Mr Mackay’s influence in the SNP over the years has been enhanced by his role as chairman and business convener, which has taken on in addition to his ministerial duties, and which has included fronting party conferences, overseeing party administration and co-ordinating election campaigns.

He served in the post between 2011 and 2018 – a period in which party membership increased from 20,000 to more than 120,000.

As one of his colleagues concluded: “He knows everyone in the party, gets on with everyone and works hard.”

Another added: “You don’t get finance if you are not a safe pair of hands. He would chat to anybody, he is not aloof. He’s generally a pretty social person.

“I think he is one of these people that generally gets on with people outside of the chamber.”

That includes opponents, one of whom described Mr Mackay as being generally “respected”, and as being considered a “tough” negotiator during Budget talks.

You don’t get finance if you are not a safe pair of hands.”

The MSP for Renfrewshire North and West is savvy enough to know that reputations can change fast in politics, however, particularly when you are in charge of multibillion pound budgets.

As he prepares to outline his spending plans for the coming year, he might recall one of the three chancellors who have been in post at Westminster during his time as finance secretary, one of those he credited with helping to cure his imposter syndrome.

George Osborne, who remained in office for a few months after Mr Mackay was appointed in 2016, had been considered a master tactician and the favourite to succeed David Cameron as prime minister until his disastrous Budget in 2012.

The set-piece was branded an “omnishambles” and resulted in humiliating U-turns having to be made on a series of measures including the “charity tax”, “pasty tax” and “caravan tax”, while the former Tory MP also endured the booing of spectators at the Paralympic medal presentation ceremony later that year.

It took Mr Osborne years to recover his reputation, and Mr Mackay has already had a taste of the kind of controversies that can follow spending announcements, although not to the same extent.

His first Scottish Budget, outlined at the end of 2016, became completely overshadowed by a massive row over a revaluation of business rates, which lasted several months and was particularly intense in the north-east, where assessments had been made before the global oil price crash stunted the local economy.

The dispute erupted just a year after the emergency closure of the Forth Road Bridge in December 2015 plunged the career prospects of Mr Mackay, who was transport minister at the time, into jeopardy.

However, he held his nerve and survived the temporary bridge closure, and the notoriously tricky transport brief in general, and in the process convinced many, including Ms Sturgeon, that he had what was required to step up to the key finance post, when John Swinney moved to education.

The fall-out from the last two budgets, which Mr Mackay has steered through parliament by striking deals with the Greens, has been dominated by a row about historic changes to income tax, which have set Scotland’s fiscal system on a different course from the rest of the UK.

But, once again, each controversy has eventually subsided, and Mr Mackay has emerged from the other side, with his reputation intact, or even enhanced.

The expansion of his brief to add “economy and fair work” to his “finance” role in 2018 has ensured that Mr Mackay has thrust in to the centre of even more crises than before.

The closure of the Michelin plant in Dundee, the uncertainty over the future of BiFab yards in Fife and Lewis, not to mention Prestwick Airport and the Ferguson shipyard, are just some of the issues to have landed on the finance and economy secretary’s desk.

There will be many more twists and turns to come for Mr Mackay, on these protracted problems, and countless others which are yet to emerge.

If he is to ultimately take the next step in his career he will have to keep thriving by surviving, whatever such obstacles are put in his way, and that is no easy task.

To date, however, there has been little evidence to suggest that Mr Mackay feels out of his depth in the most prominent positions of power, whatever he says himself.