Since it was announced we should all stay indoors, avoid meeting our friends and family and help safeguard our NHS, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has been seemingly omnipresent.

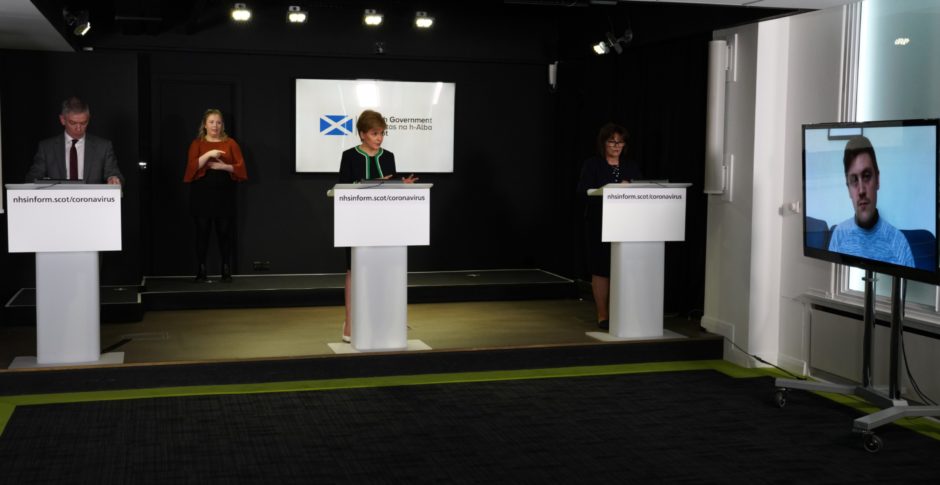

Nearly every press conference, briefing, video call, interview and question session has been hosted by the first minister.

Cabinet secretaries have been present, alongside our scientific, economic and medical experts. But at each session, in each press release, Ms Sturgeon’s has been front and centre.

It is not unexpected for a political leader to front a campaign or deem themselves responsible for every decision, even in our own parliamentary democracy.

But could this, in fact, be an example of the first minister struggling to delegate?

Struggling to delegate

Boris Johnson’s UK Government, even before he became ill, allowed cabinet ministers the chance to lead press conferences.

Ms Sturgeon, on the other hand, has fronted every press conference since the pandemic forced the majority of us to stay inside.

On top of that, she has attended Cobra (Cabinet Office Briefing Rooms meetings) with the prime minister or UK cabinet ministers and continued to meet constituents needs.

On Thursday, she took part in what could be described as a small piece of Scottish political history (but what isn’t these days) with the inaugural “virtual” first minister’s questions.

Via the medium of Zoom, the leaders of Scotland’s other political parties took turns to scrutinise Ms Sturgeon over the government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic – in a similar vein to regular FMQs, but from each politician’s living room instead of the chamber at Holyrood.

All the same, like with each appearance at the daily press conference, it means Ms Sturgeon is the conduit for all questions and, on the face of it, responsible for each answer.

A “workaholic”

One government insider suggested it was in Ms Sturgeon’s nature to oversee every detail of her brief, to the point where it seems she is a “workaholic”.

“She is someone who takes the responsibility of leadership very seriously,” he said.

“This is underlined by the fact she hasn’t taken a day off since or ducked out of an interview since this all kicked off.

“This is quite personal, particularly for a first minister who has been in office for as long as she has.

“You could describe the first minister as a Rolls-Royce of a politician… even if the BMWs and Mercedes are good, they could not perform at such a high level for the length she has. The first minister just keeps going.”

Stresses of leadership

Despite each political leader’s backing of Ms Sturgeon to steer the country through the crisis, the first minister’s time during the coronavirus epidemic has not been without its political problems.

Foremost was the revelation her Chief Medical Officer, Dr Catherine Calderwood, had “escaped” the confines of her Edinburgh pile on two consecutive weekends to visit her Earlsferry holiday home – a direct flouting of the rules she put in place.

Insiders said the two had a “good rapport”, with Ms Sturgeon keen on taking the CMO’s advice on how to handle the ensuing pandemic.

The first minister even went as far as to say she hoped she would not have to accept Dr Calderwood’s resignation.

Insiders suggest the decision on the resignation would have been easier on the first minister if Dr Calderwood had been a politician, adding “she would have been able to do that pretty promptly, the news cycle would likely have been shorter too”.

Had the coronavirus not dominated our lives, another news story invariably would have.

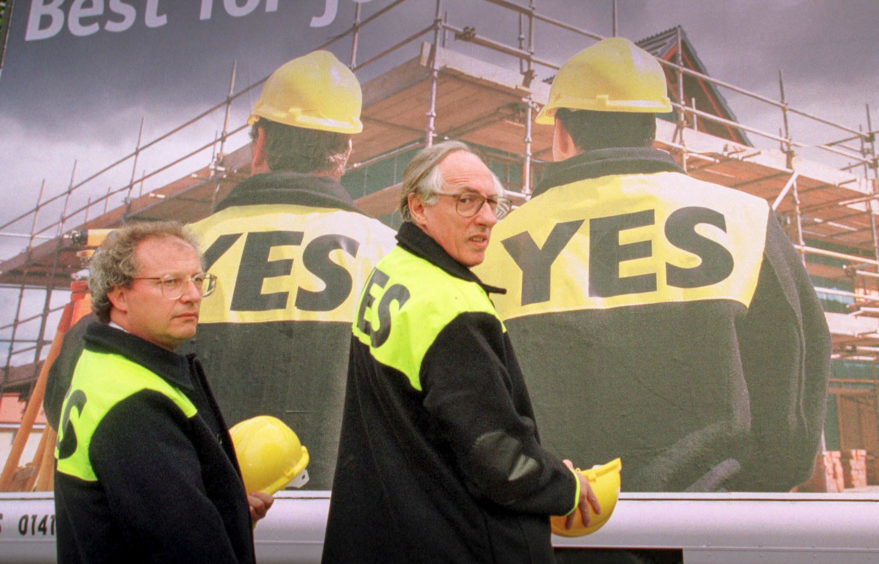

The trial and acquittal of Ms Sturgeon’s one-time mentor and boss, Alex Salmond, would have taken over the front pages and airwaves the same way Covid-19 has.

Following the trial, the first minister said she was a “strong believer” in “rigorous, robust independent judicial process where complaints of this nature, if they come forward, are properly and thoroughly investigated” and that due process “takes its course”.

She admitted there would be further discussions on the trial, once the coronavirus crisis had abated.

Mr Salmond, following his being cleared, said he has evidence he hopes to show. This has been picked up by his most fervent supporters as evidence of a political conspiracy against their idol.

Had it not been for the outbreak, there can be little doubt of what the country would be discussing – given the first minister herself had been set to give evidence to a parliamentary committee on the government’s handling of the initial complaint.

This, too, has been postponed until the coronavirus pandemic has been settled, but it will likely add to the increased pressure Ms Sturgeon is under right now.

Full schedule

So is the amount of work it appears Nicola Sturgeon is carrying out normal for a first minister?

The First Minister’s week follows a typical pattern, according to those who have worked with her. Monday through to Thursday, they are concerned with governmental work. On Fridays and usually Saturdays they are doing constituency work, then on Sundays, it’s media appearances for TV.

Sunday afternoons are rare moments off, but according to the insider, “they don’t get much time to themselves”.

“At UK Government level, they are sharing the workload a bit more, she is a complete ‘workaholic’ and fully focused on the day to day running of the government’s portfolio,” he added.

“The level of input she would normally have on government departments is probably less now than normal.

“These are unprecedented times, obviously. In terms of the how much the First Minister has to be seen at the front, the last thing which even slightly compares is when Grangemouth was threatened to be closed.”

In the little time she gets to herself, we know Ms Sturgeon enjoys reading, but whether the traditionally private politician is getting to thumb through many books at the moment remains to be seen.

According to the latest YouGov figures, Ms Sturgeon remains the second-most popular politician in the UK (number one being Nigel Farage) and even her fiercest critics have rallied behind her during the crisis.

Despite the CMO debacle, Scottish Conservative leader Jackson Carlaw said he still had “full confidence” in the first minister.

Evidence, then, that Ms Sturgeon has to be seen as a leader, with an emphasis on the word seen.

So what would happen should the first minister, like the prime minister, be unable to carry out her duties?

What happens if Nicola Sturgeon gets ill?

Should Ms Sturgeon become unwell to the point she is unable to carry out her first ministerial duties, it would, in the first instance, be for the presiding officer of the Scottish Parliament, Ken Macintosh, to decide who would designate who would carry out the role.

The presiding officer cannot appoint a first minister – only the Queen can, under the terms of the Scotland Act.

He would discuss with the government and all of the parties represented at Holyrood on how to proceed – it being entirely unlikely he would act “unilaterally”.

The government source pointed out it would fall to deputy first minister John Swinney to take on the responsibility, confirmed earlier this week by Ms Sturgeon.

Already Mr Swinney is said to have taken “a more hands-on approach with MSPs and the day-to-day stewardship of the party” as a result of Ms Sturgeon’s focus on guiding the country through the pandemic.

Mr Swinney would have the ability to carry out the duties of the first minister but, as mentioned, he would not be first minister.

Should Mr Swinney then become ill, it would be again up to the presiding officer to designate someone to replace them.

The presiding officer could also opt to rely on “collective government”, meaning there would be no-one filling in for the role of first minister and allowing the cabinet to conduct the business of governing during the period.

A spokesperson for the Scottish Parliament said: “If the first minister is unable to perform her functions, those functions can be carried out by another member designated by the presiding officer.

“If that member became unable to act for the first minister, the presiding officer could make another designation.”

Precedent

A designated first minister has been utilised before, in 2000 in the early years of the Scottish Parliament.

Presiding officer David Steel nominated Jim Wallace to exercise the functions of the First Minister when the late Donald Dewar underwent planned heart surgery and recuperated.

Mr Wallace was deputy first minister but, differently, leader of the Scottish Lib Dems, who were in a formal coalition with Mr Dewar’s Scottish Labour party at the time.