They say a week can be a long time in politics, but that is not the case for those who have the unenviable task of organising elections.

For the thousands who work behind-the-scenes so that millions more can exercise their right to vote, even 12 months is extremely short notice to start rearranging long established plans and protocol.

That is why alarm bells are already ringing about the potential impact of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic on the next Scottish Parliament elections, which are currently due to be held one year from Thursday.

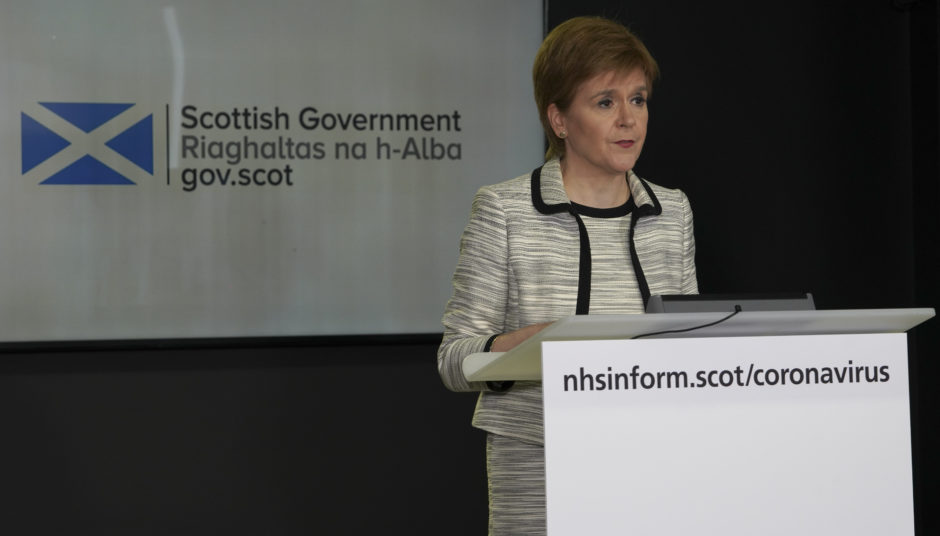

Questioned about the issue last week, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said she did not have “space in my head to think about politics or elections” during the ongoing crisis.

But, with rumours rife that the contest could be delayed or carried out entirely by postal ballot, the SNP leader did admit there could be “different ways of conducting the election”.

Privately, discussions about the arrangements for the poll will certainly be more advanced.

Officials in the Scottish Government’s elections team, as well as the Electoral Management Board for Scotland and the Electoral Commission Scotland, are believed to be mapping out potential contingency plans just now.

“We are actively planning for the Scottish Parliament election to take place in May 2021,” said the Electoral Commission Scotland.

“However, we are keeping under review the potential impact of Covid-19 and will continue to advise governments and the electoral community on any implications for the planned polls.”

Emergency legislation has already enabled councils to postpone by-elections, and a further Act of Parliament would be required to move the date of next year’s Holyrood vote, if the delay was to be longer than one month.

This democratic dilemma is one of the many side-effects of the coronavirus emergency, and it is causing headaches for governments and parliaments around the world, not just Scotland.

The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance has reported that, between February 21 and April 29, a total of 52 countries postponed national and local elections due to the pandemic.

Italy, Spain, France, Germany, Serbia, Austria, Switzerland and Romania were among those delaying votes.

Another was England, where local and mayoral elections, including in London, were due to be held this month but have now been put off for a year, and could go ahead at the same time as the Holyrood vote, if it is not rescheduled.

However, 19 countries decided to proceed with electoral contests, nine of which were nationwide votes.

South Korea was the first major democracy to hold a general election in the middle of the crisis on April 15.

It passed without any major incidents, although 30 million voters were asked to clean their hands with sanitiser, wear face masks and plastic gloves, stand at 3ft apart, and have their temperatures taken, with high temperature resulting in a requirement to vote in separate booths that were then disinfected.

Arrangements elsewhere have been less smooth, however, with Poland poised to press ahead with an election by postal ballot this month, despite calls for a boycott amid widespread condemnation of the move, which has not been approved by parliament.

Newcastle University-based political scientist and author Alistair Clark has written about the potential consequences of the pandemic on elections in the longer term.

“There has been a mixture of responses across the world. There has not really been a consistent way of doing this,” he told The Press and Journal.

“I think everybody is really learning in relation to election delivery at the moment, and thinking about how to do it safely.”

He believed the coronavirus was going to “focus minds on how elections are organised and run”, including in Scotland.

“There may be opportunities to rethink how we do elections at the moment,” he said.

“I think postal voting will be discussed far more seriously as we head towards the election, of that I am absolutely confident.

“There is not enough time to organise online voting, but for the likes of postal voting, there are already established procedures.

“What would be required would be a scaling up of that quite considerably, because I think only 18% of the electorate actually were registered for postal votes at the last Scottish Parliament elections.”

Ms Sturgeon raised the prospect of postal votes being used when she was asked about the election last week, saying: “My starting point is that the election should go ahead. It may be that there needs to be certain different ways of conducting the election, postal voting, but the election is still quite a long way away.”

But while postal voting would remove most infection risks for voters, it might not protect the army of people employed by councils to count the votes in sports halls across the country.

Potential problems recruiting staff to conduct the count could prove to be another issue if the coronavirus continued to be a concern in the run-up to the election, according to Mr Clark.

“It’s quite possible to see that being under quite a bit of pressure at an election held under pandemic circumstances as well,” he said.

Christopher Carman, the Stevenson professor of citizenship at Glasgow University, believed a postal-only election might be even more complicated than delaying it.

“The Scottish Parliamentary election can be rescheduled and there is precedent for that,” he said.

“A shift to all postal voting would likely be a slightly larger task than ‘simply’ postponing the election for a year, but it is something that many places, including states in the US, are looking at.

“An issue with a complete shift to a full postal vote is that it requires a substantial administrative investment, so it would have budgetary considerations that would need to be taken into account.”

At a UK Government level, there are also thought to be concerns about the potential for a new voting method to be introduced in Scotland but not elsewhere, in addition to the already different electoral system at Holyrood when compared to Westminster.

Politics, as always, has the potential to complicate matters further, however.

The SNP would want to secure as much of a consensus as possible about the way forward, but the timing of the election could become a factor in the result.

In South Korea, President Moon Jae-in is said to have won a decisive victory in last month’s election as a direct consequence of his government’s handling of the crisis, having appeared destined for defeat as recently as January.

Opposition parties, who say they have yet to be contacted about any change of plan, might therefore be forgiven for privately preferring a delay to a postal-only election.

But a year is a long time in politics, even if those organising the election might think otherwise.