A series of polls has shown rising support for independence and Nicola Sturgeon has vowed to put a second referendum at the heart of the SNP manifesto.

Already the SNP plans for indyref2 are fast becoming the defining issue of next year’s Scottish election.

With that in mind, here is a look at some of the issues on how a second vote should be set up in terms of voter eligibility, the question (or questions) and the winning margin.

Who should get to vote?

At the first independence referendum, in 2014, the Scottish Government successfully extended the franchise to include 16 and 17-year-olds, despite concerns from pro-UK supporters that teenagers would be more likely to support independence.

Of the record 3.6 million voters who voted in 2014, around 100,000 were aged 16 to 17. Subsequent research suggested 71% voted for independence.

Since then 16 and 17-year-olds have been added to the franchise in other Scottish elections. Voting rights have been extended to citizens of all nationalities legally resident in Scotland including refuges and those granted asylum. Existing voting rights for EU and Commonwealth citizens have been reaffirmed. While prisoners serving fewer than 12 months are now allowed to vote.

Conventional wisdom suggests that a referendum would simply adopt the existing franchise for Holyrood elections.

But there have been suggestions that voting rights should be extended to people born in Scotland but now resident elsewhere in the UK.

His remark was pounced on by the SNP, who claimed the suggestion that the pool of voters should be widened was gerrymandering.

It has been assumed that Scots based elsewhere in the UK would be more likely to vote against independence.

Baroness Taylor attempted to amend legislation as it went through the House of Lords to open up the referendum to people like her. Her bid ultimately failed.

How should the question be worded?

The wording of referenda often prove contentious.

In 2014 Scots were faced with a ballot paper that asked them to answer either Yes or No to the question: “Should Scotland be an independent country?”

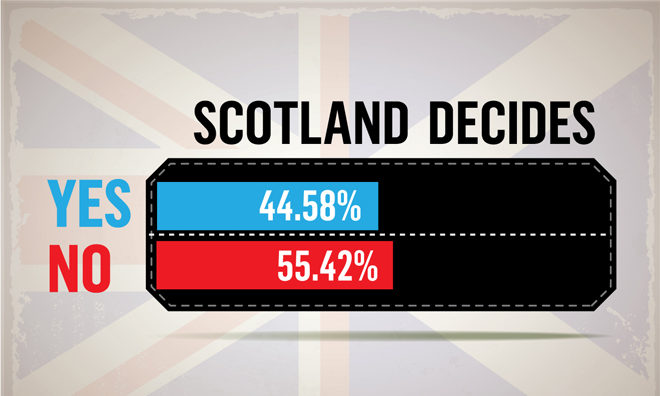

As history tells us, the No side won with 55% of the vote and Yes recording 45%.

That in itself was controversial with some claiming it gave the pro-independence side an in-built advantage because voters would be attracted to Yes as a more positive word.

Originally it had been proposed that the 2014 question should be: “Do you agree that Scotland should be an independent country?” It was a form of words supported by the SNP.

However, an Electoral Commission assessment recommended that “the question is redrafted to ensure that it is asked in a more neutral way that avoids encouraging voters to consider one response more favourably than another”.

Similar arguments raged over the form of EU referendum question. Ahead of the 2016 EU poll, the Electoral Commission rejected a question format that asked for a Yes/No answer on the grounds that it might favour one side.

So, in 2016, voters were asked: “Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?”

They then had to tick one of two boxes, which said: “Remain a member of the European Union” or “Leave the European Union”.

Despite Leave winning the referendum by 52% to 48%, some pro-UK supporters have suggested altering the question for indyref2 to ask voters to choose between leaving in the UK or remaining in the UK.

The Electoral Commission has indicated that it would like to review the Yes/No question of 2014 in the event of indyref2. But the Scottish Government takes the view that the original format should be used again.

Should there be more than one question?

Ahead of the 2014 independence referendum Alex Salmond had lobbied for a second question to be included on the referendum ballot paper. The second option would be for devomax, a constitutional settlement that would give Holyrood more powers but fall short of outright independence.

David Cameron insisted that there should only be one question on independence in the negotiations leading up to the poll. The then-prime minister was of the view that one question would settle the matter properly and did not allow Mr Salmond to have a devomax consolation prize.

In talks between the UK Government, Mr Cameron got his way in return for Mr Salmond extending the franchise to 16 and 17-years and the Scottish Government getting its way on when the vote was held.

The 1997 referendum that led to the establishment of the Scottish Parliament was an example of a multi-option referendum. The first question was on whether there should be a Scottish Parliament and the second was on whether it should have tax-varying powers. In the event, both propositions were passed by the Scottish electorate – by 74.3% and 63.5%, respectively.

After the precedent created in 2014, it is difficult to see how any future independence referendum would be anything other than a single-question poll.

What about ‘super majorities’ or turn-out thresholds?

In order to win the 2014 Scottish independence referendum and the 2016 EU poll, the victors had to surpass 50% of the vote.

It has been argued that on such issues of such importance that a higher threshold, or so-called “super majority”, should have to be achieved in order to bring about change from the status quo.

Those in favour of a “super-majority” argue that higher thresholds of, say, two thirds of the vote are often required to change the constitution of clubs and other institutions.

Super-majorities in the UK are rare, but a recent example was when the House of Commons voted by 522 votes to 13, significantly surpassing the two-thirds super-majority required by the Fixed-term Parliaments Act.

From Scotland’s point of view, perhaps the most controversial constitutional poll was the first devolution referendum of March 1979. A narrow majority (51.6%) voted for devolution.

Despite the outcome of the poll, devolution was not delivered because a turn-out threshold was not reached.

The Labour MP George Cunningham, who was opposed to devolution, amended legislation so that at least 40% of the total electorate had to vote Yes for devolution to succeed. The turn-out was 62.9% but the Yes vote amounted to just 32.9% of the total electorate.