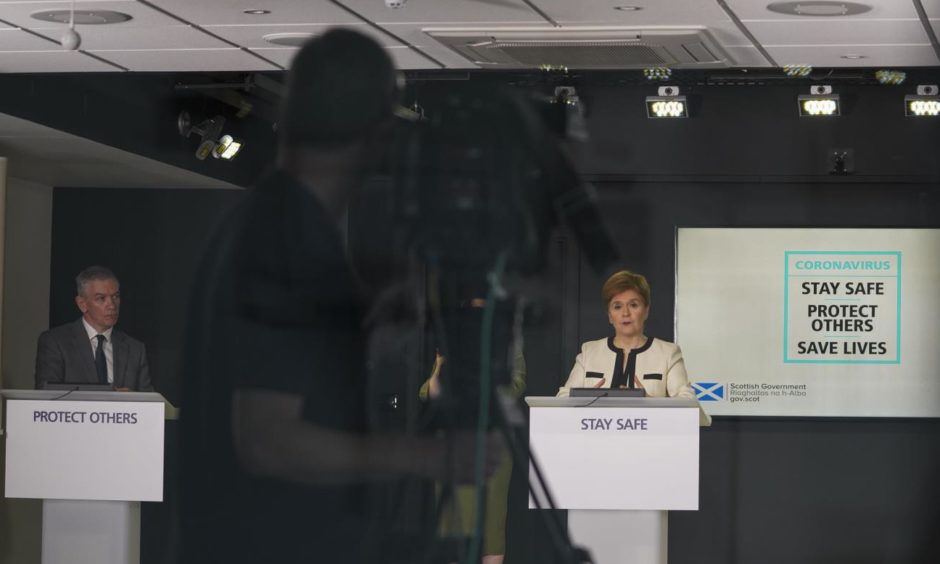

Nicola Sturgeon has won plaudits for her communication skills during the pandemic and her daily coronavirus briefings became an enduring part of many of our lives in 2020.

An almost ever-present throughout the shifting sands of Covid-19, many of the biggest moments of the past year have been punctuated by a regular update on the latest virus figures and the first minister thanking the public for tuning in.

From the impending departure of chief medical officer Catherine Calderwood to heated rows between Scotland’s two governments over funding and support, the broadcast has often been must-watch television.

It has been controversial, too, with some suggesting the briefings have at times been too political and the coverage, almost always led by SNP leader Ms Sturgeon, may have given the party an unfair advantage in the polls.

With no more briefings until after Christmas, we take a look back at how the landscape of the pandemic in 2020 impacted on the language, attendees and controversies of the Scottish Government’s daily updates.

Who appeared

The briefings have been shown live on television almost daily since March and have featured a recurring cast of some of Scotland’s most important political figures.

It is no surprise that Nicola Sturgeon has attended the most over the past nine months, appearing 151 times – more than twice as much as chief medical officer Gregor Smith and health secretary Jeane Freeman, who came in joint-second place.

Dr Smith, who replaced Catherine Calderwood in the job after she was found to have visited her second home in Fife in an apparent breach of lockdown rules, made a total of 69 appearances as he was tasked with explaining some of the finer medical points.

The race for second place was neck and neck in the weeks leading up to Christmas, with health secretary Jeane Freeman, who at times stepped in for the first minister to lead the briefings, eventually chalking up the same 69 appearances.

Professor Jason Leitch, Scotland’s national clinical director, has held a strong presence during the pandemic and appeared in the fourth-most broadcasts, at 54.

The briefings have been dominated, as one might expect during a pandemic, by politicians and medics but others have also played a role.

Police Scotland’s chief constable, Iain Livingstone, has appeared eight times so far, often to provide updates on how officers will tackle challenges such as Halloween, travel bans, house parties and bonfire night in the midst of the pandemic.

Making just one appearance each were Martin Blunden, chief officer of the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service, NHS Louisa Jordan chief executive Jill Young, Scottish Government chief economist Gary Gillespie, and Benny Higgins, who chairs the Scottish Government’s advisory group on economic recovery.

What was said

Analysis of transcripts of the first minister’s statement at the beginning of each of the briefings gives us some insight into how the language used has been influenced by major events and incidents throughout the pandemic.

Key words such as ‘restrictions’ reach a peak at the tail end of the first wave, around April and May, and then again around October, in the middle of the second wave, as ministers pondered how to keep outbreaks under control.

Aberdeen dominated the discussions in August after a cluster of cases linked to pubs and restaurants saw the city sent into Scotland’s first localised lockdown.

The move, which saw a five-mile travel limit introduced and the closure of all hospitality, was controversial and led to accusations that the Granite City was being treated unfairly in comparison to the central belt.

The same month it emerged Aberdeen FC players breached coronavirus protocols to visit a city bar, leading to warnings that the professional game in Scotland could be put at risk by any further incidents.

We also found a shift in the language used by Nicola Sturgeon to describe the situation as months went by, with April being the most “difficult” month and the winter bringing an increased use of the word “tough”.

While there were warnings of “hard” times ahead in the summer, the first minister’s choice of language indicates there was still a feeling of “hope” as the number of new cases began to decrease and restrictions were eased.

Use of the word restrictions was at its peak at the tail end of wave one and the middle of wave two.

Aberdeen dominated many of the August briefings as cases surged.

Whilst April was the most difficult month, the winter was the most tough…

…and while the summer was still hard – there was also hope.

Controversy

The daily briefings were the source of some controversy over claims the first minister used them too often as a political platform, potentially in breach of impartiality rules.

Ms Sturgeon used the slot to accuse the UK Government of “negligence” in the face of Russian interference, to criticise Boris Johnson’s switch to a ‘stay alert’ lockdown slogan as “vague” and “imprecise”, and to hit out at his former aide, Dominic Cummings.

The departures from the coronavirus topic, which were often as a result of questions from journalists, saw Labour peer Lord Foulkes call on Ofcom to investigate the broadcasts, which he believes should instead be carried out by a public health official.

Lord Foulkes suggested the format of the briefings “constitutes an outrageous breach of the impartiality rules” as Scotland prepares for next year’s Holyrood elections and called on the watchdog to make a ruling over the issue.

Ms Sturgeon responded to some of the criticism at a briefing last week, stating Lord Foulkes “has never wanted these briefings to happen”.

She said this is “regrettable because it suggests that political considerations are more important than the vital imperative of communicating directly to the public in a public health emergency.”

Scottish Conservative leader Douglas Ross also claimed in September that the briefings “more often than not” strayed beyond matters of public health and were used to criticise Boris Johnson or UK ministers.

Editorial merit

The BBC said later the same month it would no longer provide live coverage of every briefing and would decide whether it should be televised based on “editorial merit”.

“We will of course consider showing press conferences live when any major developments or updates are anticipated,” a BBC spokesman said.

The broadcaster later announced a U-turn on the decision following anger from politicians and some members of the public.

Ms Sturgeon has repeatedly insisted her daily briefings are not intended as political set-pieces and are useful for older or vulnerable people who may have limited access to information on the pandemic.

What has struck me during the period these briefings have been televised, is they have been particularly important among some sections of the population who don’t routinely go on the internet or watch things on their phone – and that tends to be older people.”

Nicola Sturgeon

But the criticism does appear to have shifted the tone of the briefings in recent weeks, with the first minister now occasionally declining to answer a question in detail if it is not closely enough related to the pandemic.