Dundee council chiefs admitted they never apologised to the family of a tragic two-year-old who died while in care in the city.

A top official was quizzed about the 1960 death of Alexina Kelbie during a hearing of the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry on Thursday.

She suffered a head injury at her foster home in Dundee’s Fintry Road which was initially claimed to have been self-inflicted.

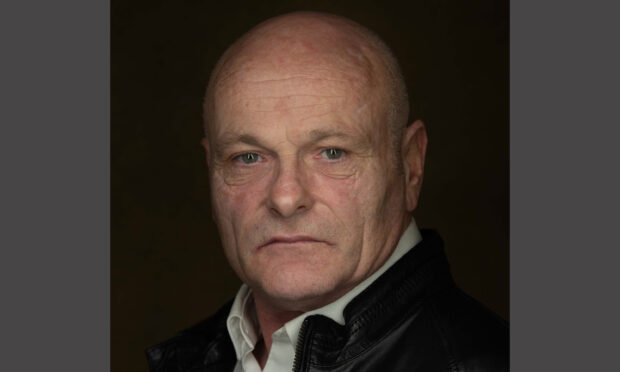

The toddler’s brother Peter Kelbie, originally from Aberdeen, has spent several decades fighting for answers explaining what happened to Alexina.

Police Scotland finally apologised to him last year after they admitted they had not alerted him to new evidence which emerged in 2006.

A Dundee University expert had re-examined post-mortem photographs and found evidence suggesting she had been assaulted.

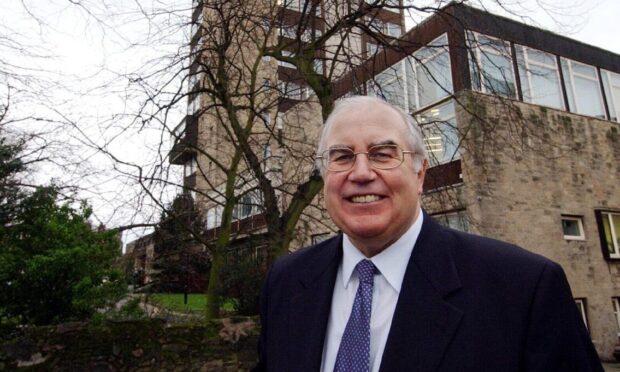

Glyn Lloyd, head of the children’s service at Dundee City Council, was asked about the child’s death while giving evidence to the inquiry, which is chaired by Lady Smith.

He said the local authority could find no files relating to Alexina’s care.

Ruth Innes KC, the inquiry’s senior counsel, asked Mr Lloyd about the council’s contact with Mr Kelbie.

He said there had been “correspondence over the years”, involving both the former Tayside Regional Council and Dundee City Council, and that the authority had helped fund a memorial to Alexina.

Following the recent evidence relating to her injuries, Mr Lloyd said: “The council wrote back and offered sympathy… and encouraged him to make contact with the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry.”

No apology

When it was put to the official that there had been sympathy expressed but no apology, Mr Lloyd said: “There was an acknowledgment she died in care but there wasn’t an apology.”

Mr Kelbie, who was also in care in the north-east as a child, only learned of Alexina’s existence and death in 1983 when he was reunited with his other birth sisters in London.

He pushed for reviews into the police investigation in 1988 and 1993 but it was decided the death had been fully investigated.

However, in 2006 Mr Kelbie asked to see the police files from 1960 which prompted another investigation.

This time a detective found post-mortem photographs of Alexina which showed her body was covered in bruises and other injuries, including a bite mark.

Officers traced the photographs back to Sergeant John Underwood, who said at the time he was unhappy with the suggestion Alexina’s injuries were self-inflicted.

Pathologist Professor Derrick Pounder from Dundee University reviewed the photographs, however his findings were not disclosed to the Kelbie family at the time.

The force admitted last year it withheld the information about this development in 2006, and has since issued an apology to Mr Kelbie and his family.

Six children in one bed

Mr Lloyd was also questioned about several other abuse cases involving children who were put into foster care in the 1960s through to the 1990s, most of which predated his time with the service.

It included a situation where five members of the same family were placed with a foster carer in Broughty Ferry.

Six children ended up sharing one double bed, and were expected to carry out work serving construction workers who were also lodging at the home at the time, while building the Tay Bridge.

Another harrowing case involved evidence from a witness known as “Anthea”, who grew up in Dundee but was fostered with a family in Fife.

The couple had four children of their own, and took in four foster children.

Mr Lloyd said such an arrangement would only be considered suitable now in an “extraordinary set of circumstances”.

At one point the carers went on holiday to England, leaving their 16-year-old daughter in charge of seven children.

“It’s completely inappropriate and somewhat of a mess,” Mr Lloyd told the inquiry.

In 1978, it was reported to social workers that a 15-year-old son of the carers had been “creating trouble at school”, including an incident on a school bus in which a girl’s clothes were “interfered with”.

Professionals discussed the safety of the foster children but did not remove them.

‘Tolerating an unacceptable situation’

“If feels like they are tolerating an unacceptable situation and waiting for it to become catastrophic before doing anything that is an appropriate response,” said Mr Lloyd.

After a number of further “disturbing incidents” involving the boy, it was still deemed by a majority of the child protection professionals that no action was necessary.

Anthea later confided in a friend that she had been sexually abused by both her foster father and his son.

The police were contacted and she was interviewed and medically examined.

She was initially taken back to the foster home before being removed the following day.

Lessons to be learned in Dundee

Asked about his reflections on all the evidence relating to Dundee, Mr Lloyd said: “My reflections are that I think arrangements are very different in a general sense than they were 20, 30, 40 years ago, and even 10 years ago.

“Assessments of potential foster carers are much more rigorous and the subject of scrutiny.”

He added: “But I think there are lessons to be learned. First and foremost we need to continue to be absolutely vigilant at all times, and particularly listen to the views of children and young people.”

The remarks reflected evidence given to the inquiry on Wednesday by Kathy Henwood, chief social work officer at Fife Council.

She said: “The voice of the child has to take precedence over everything.”

Ms Henwood added: “I think that’s the bit we need to build into care planning and children’s rights, because children will only say what they feel safe enough to say, and we need to start developing that culture that children and adults can come and talk to us.”