Twenty years after devolution, with the ongoing focus on the UK Tory leadership contest and divisions over Brexit, what does Labour have to do to revive its fortunes? Here, Michael Alexander chats to former Scottish Labour leader and former First Minister Henry McLeish to hear his concerns about the future.

He is the former professional football player who went on to become leader of Fife Regional Council and spent 16 years as either MP or MSP for Central Fife – including a spell as Scottish Labour leader and First Minister.

But having been a member of the Labour Party for almost 50 years, Henry McLeish has warned that the party he loves is in the midst of a “catastrophe” that could end any chance of it returning as a political force.

Mr McLeish was born in Methil a quarter mile from what is now Keir Hardie Street – a residential area named after the founder of the Labour Party.

Growing up in what was then a strong mining community, his family were socialists, and in those days, as Henry puts it, the strong socialist traditions of the mining communities meant voting Labour was “as easy as breathing”.

Yet in recent years, with the old industries long gone and the “community of interests” that went with them broken, former Labour heartlands such as those covered by his old Central Fife seat have been claimed by the SNP.

While Shadow Scottish Secretary Lesley Laird narrowly won back Gordon Brown’s old Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath seat for Labour at the 2017 General Election, the recent European elections saw Scottish Labour’s worst ever election result across the country with the SNP claiming 38.7% of the vote, Brexit Party 14.8%, Lib Dems 13.8%, Conservatives 11.6% and Labour polling just 9.3%.

Indecisiveness over Brexit has been blamed for Labour’s latest pummelling following years of domination by the SNP at Holyrood and latterly by SNP MPs at Westminster.

But as debate continues over the future direction of Labour, Mr McLeish has warned that unless the party comes up with its own clear identity and vision, it may find no way back at all.

“The first important thing to say is that society has changed, technology has changed, employment has changed, the workplace has changed,” said Mr McLeish in an exclusive interview at his home in Fife.

“And I suppose in a sentimental way that sense of emotional attachment to politics has all disappeared. It’s important to say that it’s very difficult to compare eras.

“But despite the problems today, I’m still very committed to the ideas, thoughts and principles that fired the Labour movement in 1900 – things like justice, equality, fairness in the workplace.

“These are as relevant today as they’ve ever been – possibly even more so. And that’s why I still have hope.”

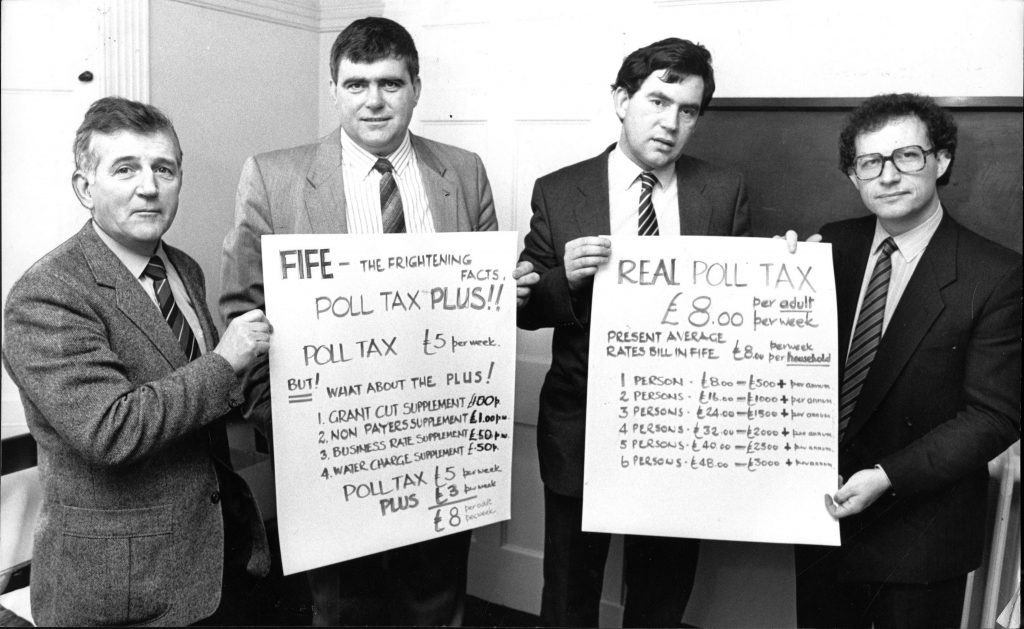

Mr McLeish, who was forced to resign as First Minister in 2001 amid the “muddle not a fiddle” Officegate scandal, looks back proudly to his time at Labour-run Fife Regional Council in the 1970s/80s when the Kingdom became the first local authority in Europe to introduce free transport for 50,000 older people and was regarded as the best education authority in the UK.

The priorities of the council then were built on that “community of interests”, representing the real needs of the people, he said.

But while those core needs arguably remain the same, he says Labour has “failed to adjust the narrative for the society we live in” and has failed to accept that the sense of “entitlement” it once had in many communities has gone.

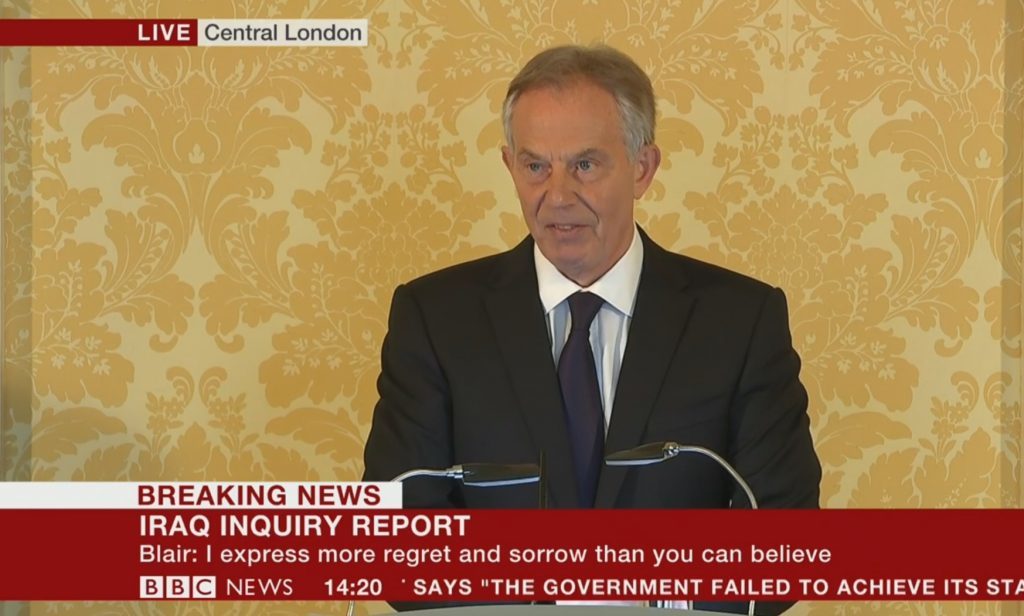

In addition to well-documented issues including fall-out from the then UK Labour government’s controversial backing of the 2003 Iraq war, Mr McLeish said many people had “recalibrated” their political allegiances against the backdrop of a “UK in decline”, a “poisonous atmosphere” post-Brexit, absent social cohesion, decimated pay and pensions and the “lagging effect” of the 2008 financial crash where millions had realised the job and therefore life prospects for them and their children had disappeared.

Instead of automatically voting Labour, people have “broken their links and will vote for their own needs, ideas and concerns instead”.

“A lot of them feel they’ve left the Labour Party because they feel the Labour Party has left them,” he said.

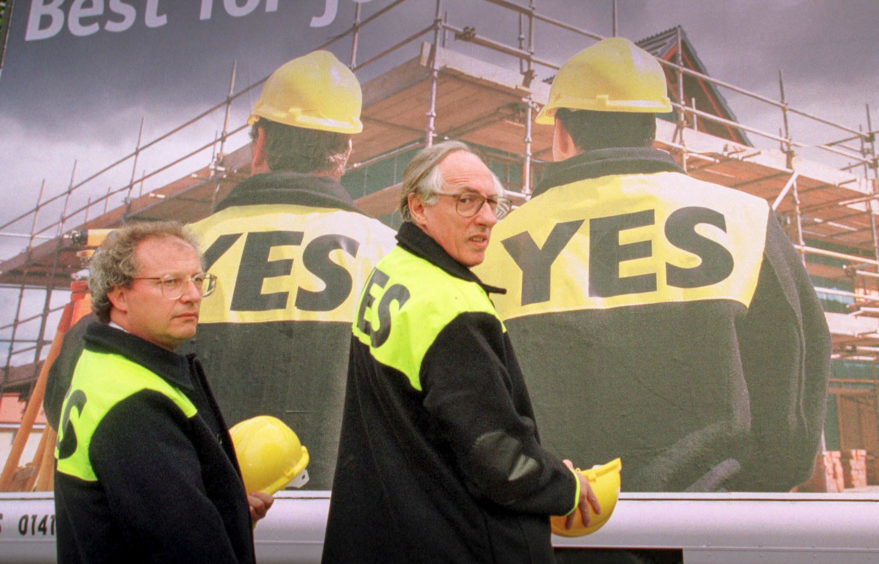

Scotland also had its own specific issues, he added. Despite delivering devolution in 1997 and the creation of what he regards as a very successful Scottish Parliament, Labour had “turned its back” on the institution – instead remaining “wedded” to Westminster – while the SNP saw devolution as a step towards its goal of independence and had capitalised.

Using a footballing analogy, Mr McLeish said there was a repeated temptation for Labour to change its leader in Scotland.

However, he believes the problems facing the Labour Party are “much much deeper”.

“Labour also has to get over the complacency that there’s some kind of socialist country up here waiting for the message from Westminster to get over the hill,” he added.

“Forget that! Because the more that we think that a Corbyn victory is going to be the salvation to all our problems, then the more trouble we are going to create for ourselves.”

Labour also has to decide what it’s position is on the Scottish constitution instead of “ignoring” the issue. Saying no to indyref2 is not a policy – it’s “incredibly negative”, said Mr McLeish, who has repeatedly said he would like federalism to be properly explored as a direct alternative to the “potential drift” towards Scottish independence.

He said there was hope for federalism because opinion polls suggested more than half of the population had not yet been convinced of the attractiveness and wisdom of independence.

However, with Scotland having always been internationalist in outlook, the pro-EU Remainer said Labour had also been punished by not being a pro-European party and blamed the “ambiguity and confusion” of Jeremy Corbyn for adding to this.

While ‘big issue’ or binary politics such as Brexit and the Scottish question had added to the decline of the party, he wanted Labour to claim ownership of fundamental issues such as climate change, renewable energy and social care.

He said there should be a Labour party commission in Scotland looking at the impact of technology, such as AI, on jobs.

Fundamentally, however, he is also a great supporter of there being an independent Labour Party in Scotland giving it “space” from the UK party and allowing it to “confront” the SNP.

With autonomy, of course, would come a lot more responsibility and the need to raise its own finances.

However, it may be the only way for the party to have a future, he said.

“I think this is a deep genuine crisis for Labour,” he added. “I think there are ways forward. I don’t think there will be a quick turn around, but there are ways. It’s like turning round an oil tanker because we’ve reached a point where we are not making any progress.

“We’ve got to take some of the right decisions now. Because this isn’t just another bad day at the office for Labour. It’s a catastrophe.”