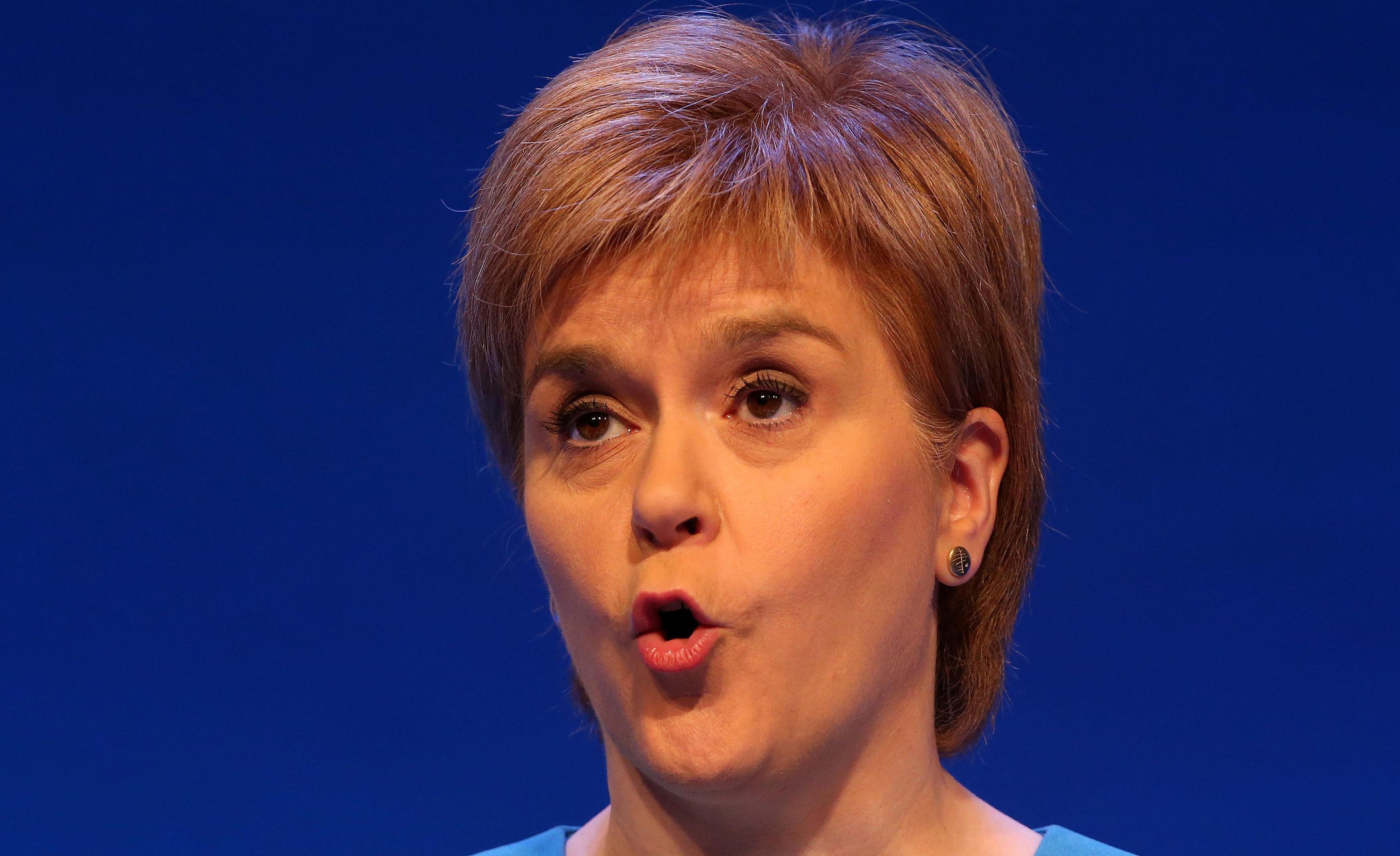

Nicola Sturgeon put herself on a collision course with millions of Leave voters by threatening to block the UK’s exit from the EU.

The First Minister accepted there would be “fury” from voters across Britain if MSPs exercised what has been hailed as a Holyrood veto on leaving the bloc.

Legal experts say there is no veto as such because Westminster could ignore the Scottish Parliament’s attempts to thwart Brexit.

Ms Sturgeon said refusing to allow the UK Parliament to assume legislating on an EU exit on Scotland’s behalf is “on the table” as an option to protect Scotland’s EU status.

A total of 62% of Scots backed staying in the bloc in Thursday’s vote.

The UK Parliament requires approval from the Scottish Parliament – under a convention known as legislative consent motions – to remove a section of the Scotland Act which demands that Holyrood laws comply with EU legislation.

Asked if she would consider asking MSPs to deny such a request from Westminster, Ms Sturgeon said: “Of course.

“If the Scottish Parliament is judging this on the basis of what is right for Scotland then the option of saying that we are not going to vote for something that is against Scotland’s interests, of course that’s going to be on the table.”

She was then asked on BBC Sunday Politics Scotland if she would pursue that course even if it blocked the whole of the UK leaving the EU.

The SNP leader replied: “Don’t get me wrong I care about the rest of the UK, I care about England. That’s why I’m so upset at the UK-wide decision that’s been taken. But my job as First Minister, the Scottish Parliament’s job is to judge these things on the basis of what’s in the interests of Scotland.”

She said she could imagine the anger from Leave voters if that scenario played out, but added: “It’s perhaps similar to the fury of many people in Scotland right now as we face the possibility of being taken out of the EU against the will.”

Ms Sturgeon said she is pursuing all options to protect Scotland’s place in the EU. She said on Firday that a second independence referendum is “highly likely”.

A legislative consent motion, also known as the Sewel Convention, allows the UK Government to make laws on matters that are normally under the jurisdiction of devolved parts of the country.

A request to take control of legislation in a particular area of devolved law should be signed off by the relevant parliament, according to convention.

Prof Sir David Edward, a former European Court judge, told a House of Lords committee in May that the UK Parliament would need an LCM from Holyrood to remove section 29 of the Scotland Act 1998, which makes Parliament bound by EU law.

He said he can “envisage certain political advantages being drawn from not acceding to the legislative consent”.

But he added the UK Government could go ahead anyway and legislate to remove the EU provisions despite a refusal from MSPs.

James Chalmers, a Glasgow University professor with expertise in Scottish law, said the LCM is simply convention rather than being legally binding.

“There is nothing in law to stop Westminster dispensing with the consent of the Scottish Parliament if it so decides,” he said.

Conservative MSP Adam Tomkins, who is a professor in public law, said it is “nonsense” to say Holyrood has the power to block or veto Brexit.

He said: “Holyrood has the power to show or to withhold its consent. But withholding consent is not the same as blocking.”

David Mundell, the Scottish Secretary and Conservative MP, said: “I personally don’t believe that Holyrood is in a position to block Brexit.”

Earlier, Ms Sturgeon fired a warning to any future prime minster who dared block Scotland’s will on independence as she said the UK we knew no longer exists.

She told the Andrew Marr Show: “The UK that Scotland voted to remain within in 2014 doesn’t exist anymore.

“And this is a case of how we best protect stability and the interests of Scotland.”