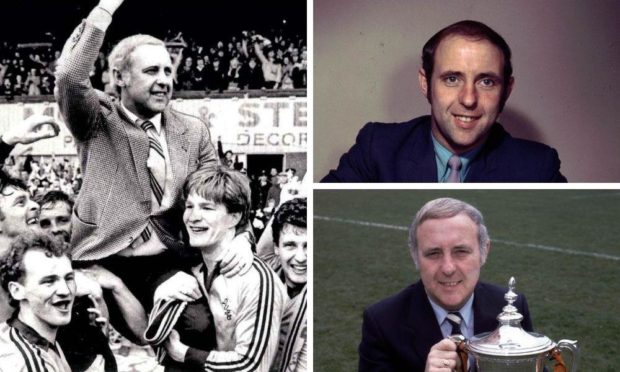

Two months on from Jim McLean’s passing, Steve Finan – author of Jim McLean: Dundee United Legend – examines just what it was that set the Tannadice legend apart as a football manager.

Jim McLean’s tenure at Dundee United is the archetypal example of what can be achieved when a talented manager is given free rein to impose his ideas of how football should be played.

Not just played by the first team of a club, but at every level from the youths upwards – and, crucially, for those ideas to be given time to mature.

This cannot be a one-way channel, of course.

The manager doesn’t merely need a vision of how he wants his team to play, he has to be able to adapt his ideas to take account of the strengths and weaknesses of the players at his disposal.

Jim did this superbly well.

His time at United can be divided into distinct (though often overlapping) phases.

He built several teams and his own football philosophy underwent several evolutionary stages to match the changing personnel at his disposal.

THE OPENING ACT

The first phase didn’t actually happen at Tannadice.

Jim’s mentor was John Prentice who had been his manager at Clyde and who brought him to Dundee FC.

The discussions on how the game should be played that these two had, added to Jim’s long-held beliefs about retaining possession of the ball, were the seeds of the style of play he would demand when he became a manager himself.

In stark contrast to what would happen at Tannadice, Prentice wasn’t given the time at Dens Park, or the free hand over all aspects of running a football club, which a manager needs to make real strides forward. Jim noted this.

He also noted the distant, employer-employee culture between directors and staff at Dens and saw something that he didn’t like, and that he knew wouldn’t work.

These beliefs, likes, and dislikes stayed with him.

When the messy departure of Prentice from Dundee was happening, Jim knew that the mutual dislike between himself and the Gellatly family in the Dens Park boardroom would never work.

Across the road at Tannadice, Jerry Kerr and the Dundee United directors knew it too.

They had watched the progress of this young coach from afar, and with Jerry fancying a move “upstairs” to a general manager-type role, the timings aligned and Jim came to Tannadice.

He brought his football ideas with him.

The first casualty of this was, to his unpleasant surprise, Jerry Kerr himself.

Jim liked Kerr, but would brook no intervention from upon high of the type that he had seen at Dens.

When asked (as is now part of Dundee United folklore) what he needed to get on with the job, Jim said “a stopwatch”.

It is a significant statement for what wasn’t said as much as what was said.

Jim would take a watch, but he wouldn’t take direction, interference, or any limits on his control of the players, tactics, training, discipline structure, or football style.

Jerry Kerr quietly left to become Forfar manager.

The reasons a change of manager was needed at Tannadice in 1971 weren’t difficult to glean.

United had several good players, but they were old, they were unfit, and they lacked ideas — the type of team that has gone stale from a lack of energy emanating from the dugout.

Jerry Kerr, after 12 years, was tired. So was his team. They had taken a 6-4 beating from Dundee, as well as going down 5-1 to both Celtic and Rangers, and 5-3 to Falkirk in the first half of that 1971-72 season.

Things improved under Jim, but only marginally.

The five goals conceded to Falkirk at Tannadice turned into a 1-1 draw in the fixture at Brockville and though defeated at Ibrox it was by the only goal of the game.

Jim had a lot to do to convince the support, and Scottish football as a whole, that he was going to be a success in his new role.

1971-75: THE FIRST TEAM

Jim built his first side (roughly 1971 to 1975) on experience.

He already had Doug Smith, Archie Knox, Walter Smith, Andy Rolland, Kenny Cameron, and Tommy Traynor. He added Frank Kopel (free from Blackburn Rovers) and George Fleming (£7,000 from Hearts) in January 1972.

The United side of 1972-73 was a different animal to that of the previous year.

Hamish McAlpine became the regular goalkeeper, Walter Smith found himself in the team more regularly and the new player discipline greatly benefited the talented, but at times wayward, Jackie Copland.

At this point, Jim was working hard on his team with repeated and lengthy drills to help them retain possession of the ball during games.

The first priority, though, was to build a solid defence. United had Smith and Copland as centre-backs, with Rolland and Kopel at full-back and Smith and Fleming screening that back four.

The team went from conceding 70 league goals in 1972-72 to conceding 51 in 1972-73. The goals scored, however, went up just one, 55 in 1971-72 to 56 the following season.

The team needed goals, because goals are gold. In United’s case, they came from “who’s that boy with the golden hair: Andy, Andy Gray”.

He was the first McLean youngster to make a breakthrough. Andy was signed from Clydebank Strollers, but pitched almost immediately from juvenile football to the First Division – and was a sensation.

Andy’s great strength was his ability in the air and Jim worked on his team to supply aerial ammunition for this spring-heeled golden boy.

United still had that solid defensive six, but going forward, the plan was for the ever-dependable Tommy Traynor and the emerging Graeme Payne to supply crosses to the large forehead of the most potent weapon in the United armoury.

Jim adapted the shape of the team and the patterns they played to get crosses into the box.

And it worked. United’s speed and guile down the flanks, supplying quality crosses, took them all the way to the club’s first ever Scottish Cup Final in 1974.

They lost to a battle-hardened Celtic under Jock Stein, but the trajectory of the club was obvious.

The real revolution in playing staff was yet to come – and it would come from the youths – but if you could point to one game that showed that Jim McLean’s way of playing football had been fully implemented then it was Saturday October 12, 1974.

United beat Hearts 5-0 at Tannadice that day with a powerful, quick-passing, rapid-attacking display.

Andy Gray only got one of the goals, surprisingly, with Tommy Traynor grabbing a hat-trick. Iain McDonald, the former Rangers winger, ripped the Gorgie defence to shreds.

It was again obvious to any spectator that this was a team, and a manager, going places.

That same season, although the overall form was quite patchy, United would “click” another couple of times and demolish Aberdeen, Partick, and Morton by four, five, and six goals respectively.

With a style of play established Jim set about improving the individual components.

EMERGENCE OF LOCAL TALENT, 1975 – 1980

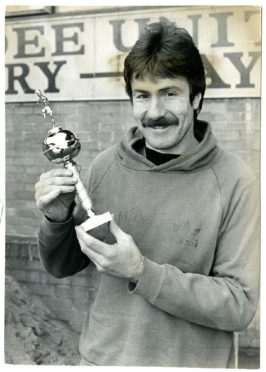

The names that came through the ranks of Dundee United’s youth system are now famous.

Any United supporter could point to Kirkwood, Holt, Sturrock, Payne, Narey, Dodds, Malpas, Milne, Stark, and many more, as the fruits of the Tannadice conveyor belt.

And it poses a question: was this a once-every-hundred-years generation of natural talent, or was this collection of mostly local boys made into a team by Jim McLean?

The answer, I believe, is very much that it was Jim’s coaching that took these laddies natural skills and made them into very good football players.

If you want proof, then consider two things:

1 – Though those players listed above were good, their collective play was great. The team was better than the sum of its parts. They played to systems designed to get the very best out of their strengths.

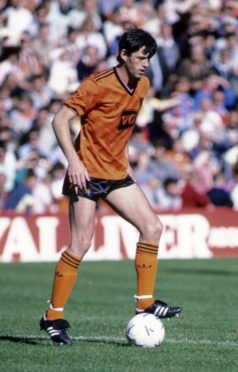

2 – Jim didn’t just improve lads he’d had since they were 12-year-olds, he improved players that came to Tannadice having spent their teenage years elsewhere. Paul Hegarty, Eamonn Bannon, Richard Gough, Jim McInally, and Dave Bowman all became better players, and Scotland internationals, because they played under Jim at Tannadice.

I’ll describe a typical Dundee United goal of this (and the slightly later) era.

Hegarty wins a long ball in the air, nodding it sideways to Narey. Big Sash plays the ball forward to Bannon on the left or Milne on the right.

They storm forward, beating men as they go or (in Ralph’s case, pushing the ball past his opponent then switching on the afterburners). Kirkwood, Sturrock and Dodds also take off on forward runs.

Gough has also dashed forward from full-back, pulling the opposing centre-half out of position to mark a man that everyone recognised as a fantastic header of the ball.

The cross comes in, Sturrock dummies, Kirkwood has a shot that the keeper blocks, and then Dodds, who has continued his forward run, tucks away the rebound.

You will notice the use of the word “forward” five times in the previous four sentences.

Because getting the ball, and players, forward at pace was the staple ingredient of a United goal. Jim McLean would be horrified by the sideways-passing nature of football in the 2020s.

He’d admire the ball retention, but be disgusted by corners that are worked back to the half-way line.

He’d be out of his dugout screaming if 20 passes were made that moved the ball less than five yards towards the opposition goal.

He’d like some aspects of a Guardiola team, but he wouldn’t stand for his own team playing that way.

His United sides always got the ball forward at pace and it can be seen in footage of the teams he built. Three or four passes would be made from defender to winger, then a cross would come into the box.

Take a look at the second goal in the 1979-80 League Cup Final.

The move is: Narey to Kopel, Kopel to Bannon, who sets off on a great run, then finds Holt, who in turn feeds Sturrock who has offered himself with a wide run.

Luggy twists, turns, and puts in a cross that Willie Pettigrew nods in. It is exciting, direct, rapid-fire football that cuts gaping holes in a high-class Aberdeen defence.

THE GLORY YEARS, 1980 – 1987

This was Jim at the height of his powers. By this point, he has the recognised 11 that will win the League.

The achievements of that side have been well documented.

That team had perfected the rapid-fire attacking system so well that they scored 90 league goals.

What isn’t quite so well-known is the structure of the club that fed players into the first team.

United had training encampments in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen, as well as Dundee, and every laddie who walked into one of those training sessions learned to play the ball in ways that would be used in the first-team.

They would get the ball forward quickly, they would make sure their passes were given so that the receiving player could shield the ball.

The 12-year-olds learned how Paul Sturrock wanted the ball passed to him. The youngsters would be, or learn to be, equally good with either foot.

They would be very fit, they would understand discipline in their personal lives, their training regimes, and their play on the pitch.

Jim was, by this point, a decade and a half into the job. His influence was felt at all levels of the club.

The groundsmen were tasked with creating a playing surface suitable for a fast-paced passing game, the most highly-paid player on the books was tasked with making that idea of a fast-paced passing game a reality.

By the time of the 1987 Uefa Cup run, Jim had modified his team again with the loss of Richard Gough, but the purchase of Jim McInally and Dave Bowman. The style of play (especially in European games) changed again.

Both of the new boys had “good engines” which meant the huge amounts of energy required for what is nowadays termed the “high press” was in the team.

Again Jim bought players then evolved United’s playing style to get the best out of their talents.

Jim knew that teams like Lens, Borussia Monchengladbach, and Barcelona wouldn’t like facing a team who put pressure on them in all areas of the pitch.

Take a look at the YouTube footage of the home leg of the R.C. Lens Uefa Cup tie of October 1, 1986.

Early in the highlights you’ll see United swarming round the French defenders who are trying to play the ball around at the back.

At one point Jim McInally, wearing No.7 that night, is so far forward he is in the opposition six-yard box cutting off the possibility of a pass back from centre-half to goalkeeper.

United were also adept, and not ashamed, to use the kicking power of Billy Thomson who could deliver a goal kick to the edge of the opposition box, turning deep defence into high attack in the space of roughly three seconds.

Again, this is Jim utilising a weapon that presented itself when he signed big Billy from St Mirren for £75,000 in June 1984.

The strikers would see Billy gather the ball and take off on forward runs, knowing that the ball was about to arrive. This is another aspect of the game that has all but disappeared these days.

CUP-TIE SPECIALISTS, 1979 – 1994

Jim McLean got United to 10 cup finals over his career at Tannadice.

The aftermath of a lost final is terrible, but the preparation, the optimism, the sheer fun of the whole town (or so it feels) turning tangerine and all pushing in the same direction, all eagerly looking forward to and preparing for the game, is a fantastic thing.

The support became used to the heady times that fall between semi-finals and finals. They are, indeed, addictive.

But you have to reach a cup final first, so how did Jim’s teams play in cup ties?

In truth, there wasn’t one particular method, though there was a theme. United played in the way that was best suited to beat the opposition but what they always tried to do was not concede the first goal.

This often meant a more cautious approach, especially early in the game, and even more especially if faced by high-class opposition.

The 1988 Scottish Cup semi-final second replay against Aberdeen at Dens, after 0-0 and 1-1 draws, is a case in point. Aberdeen, with Charlie Nicholas up front, were favourites for all three games.

Again, the footage is on YouTube to be examined. United don’t push numbers into the box at any time while the score is 0-0. Bannon plays almost as an auxiliary defender even before the goal is scored.

It is a defensive masterclass until that solitary goal, which comes after (predictably) a breakaway using the running power of Kevin Gallacher.

Jim would often preach that defence was the basis of attacks, and that the best way to score a goal was to make the ball do the work with quick, accurate passes that cut open a defence and had defenders and strikers running towards goal.

Adaptability to the game, to the opposition, to the conditions, is only possible if the players are coached to cope with multiple formations and can operate in multiple roles.

Eamonn Bannon was not a natural defender, but he was able to do the job because he was trained to do so.

Paul Hegarty was a striker of middling quality until he was converted into a defender of international class. Every youngster who “made it” through the Dundee United academy (and there was a huge number who did so under Jim) to play for the first team was moulded into a player by Jim.

If a football manager is to be measured by anything, the number of players he improved is a very good way to do it.

Jim improved every player that walked through the Tannadice gate.

LESSONS FROM JIM

Lastly, there is a modern lesson to be learned from Jim McLean’s career.

Both Dundee clubs have managers who are fairly new to the job. At Tannadice, Micky Mellon would like to build a team that can challenge for honours.

He has created a firm defence, but goals have been difficult to come by at times.

Jim McLean’s priority when he walked into Tannadice was also to shore up his defence, and everything else flowed from that. All the glory was built upon the ability to not concede goals.

He found new ways, and new players, to turn clean sheets into victories, just as Micky will do.

At Dens Park, James McPake stepped in to his first job as a senior manager from the coaching staff, just as Jim did when he left Dee for United.

McPake is still trying to find his feet and find a winning blend – and it took McLean a little while to mould a team to his liking.

Football management requires time to find players who will play to the manager’s blueprint, or large amounts of money to buy and pay players who will instantly perform to the manager’s blueprint.

There are few shortcuts. Fans have to accept that turning a football club around is a difficult task. It takes a lot of work.

And because neither of the Dundee clubs have endless amounts of cash, the only other way to build a potent football machine is to find a manager with talent, then give him, or her, time to do the job properly.

That’s what Jim McLean was given, and all would have to agree that it turned out pretty well.