The real triumph of Tiger Woods is not that he is probably the best golfer in the history of this ancient sport. It’s that he’s been that with essentially four different swings.

Woods has overhauled his mechanics – often by need due to injury requirements or preventative measures – at least five times. He’s been the official No 1 player in the world with four different swings.

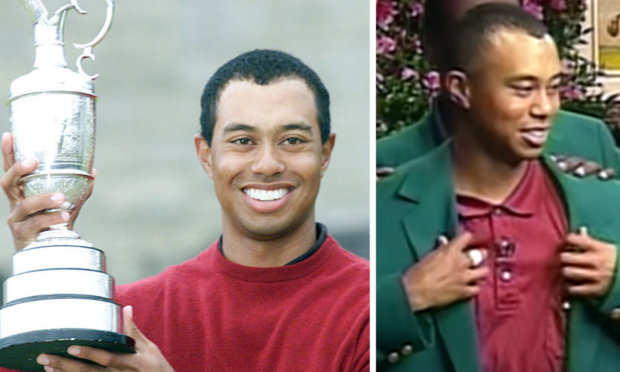

Two of those Tigers – I like to call them Version 2.0 and Version 3.0 – are also arguably the two greatest manifestations of a golfer in the 500-year history of the game. Version 3.0 was the Hank Haney-schooled Tiger of 2005 and 2006, the years of his back-to-back Open titles – he won the 2005 Masters and the 2006 and 2007 PGAs during that stretch too.

But he’s only the second best player there ever was.

The best was Tiger 2.0, dating from the decimation of the field at Pebble Beach in the 2000 US Open through to the infamous Saturday maelstrom at the Open Championship in Muirfield in 2002.

That period, of course, contains the “Tiger Slam”, when he held each of the four modern major championships simultaneously – the only player ever to do so, and featured in a new Golf Channel documentary.

It’s an entertaining romp, but without any input from the man himself, a little unsatisfying.

The Open Championship of 2000 was unquestionably a historic event but, to this witness, didn’t feel that epochal at the time. Tiger was just 24, and literally anything seemed possible – it felt that there was much more, even greater history to be written.

With hindsight, Woods’ game at the time was, as far as this intricate game with all its complex mechanics can be, virtually faultless. An oxymoron, I know, but it’s the only way to explain it.

Under the tutelage of Butch Harmon, if the wiles of weather and the essential fortunes of the game were with him (they definitely were at St Andrews) and he was in full focus, there was literally no way to stop him.

On reaching the 2000 Open, just a month after Pebble Beach, Tiger was 2-1 against in some bookies.

Against the entire field of 155 other golfers. That was daft, of course. But he was so far and away ahead of anyone else that who could dispute it?

Tiger in 2000 – noticeably slimmer to the over-muscled version of the 2010s had the arrogance of youth (too much for some in golf’s still genteel world at the time) and the mental assurance of a 24-year-old who was born for this.

He’d also by then become enamoured with the Old Course. When asked, later, to name which courses he would most like to play in the course of any given week, he replied: “St Andrews…pretty much all seven days.”

“It’s history,” said Woods in 2015.

“There’s no other golf course that can honestly say that throughout the course of history that every great champion has played.

“Old Tom Morris never played Augusta National, but every great golfer has played here. That is something no other golf course in the world can claim.”

Ben Hogan might dispute that statement – directing his private plane to fly over the Old Course while en route to the Queen Mary and home to the US after his 1953 Open triumph at Carnoustie was the closest Hogan ever got to St Andrews – but it’s certainly true of any other great player in the history of the game.

After some struggles getting accustomed to links golf – that’s a lengthy piece by itself – Tiger was ready in 2000. He’d got close in 1998 at Birkdale and should have won at Carnoustie in 1999, but for a conservative game plan. There needed to be no holding back at a wide-open Old Course.

St Andrews duly succumbed. It did so in the warmest weather for an Open in Scotland probably ever – a young US student friend who got my press courtesy pass got sunstroke – and crucially, the wind never really got up all week. Tiger always struggled in a strong links wind until much later, probably the 2010 Open, also at the Old Course – his three Claret Jugs all came in benign conditions.

Burned brown by weeks of no rain, the fairways on the Old Course were almost as fast as the greens – faster in some places. The biggest crowd in the history of the championship (still is) famously didn’t see Tiger in a bunker. But it was a close run thing; Woods admitted later his luck in bouncing over a couple of traps during the week, including on the final day.

But by then it was all done – from memory the least satisfying aspect was how easy it was for him.

Ernie Els led by a shot after the first day, a rare birdie at 17 being the difference in his 66 to Woods’ 67. But by lunchtime on Friday Ernie had flatlined with a par 72 and Tiger went to the tee with everyone knowing he was going to shoot mid-60s and the tournament was probably over.

It was a 66, and Woods led by three over David Toms. A 67 on Saturday stretched that lead out to six shots, and Sunday was just a procession. David Duval, playing with him in the final group – they were world No 1 and 2 at the time – reeled him to a lead of just three at one point, while Els, Darren Clarke and Thomas Bjorn had a wee go up the field, but Duval’s faint challenge ended with repeated howks in the Road Hole bunker.

Woods bogeyed 17 and didn’t match Nick Faldo’s Old Course record aggregate of 20-under, but the course was a good deal longer than ten years before.

He’d eviscerated the field in much the same way as at Pebble, and he got his hands and his name on the Claret Jug at last – the win completed the career Grand Slam, just three years after he’d won the 1997 Masters to start it all.

Why didn’t it last, why did we see Tiger version 3.0 just five years later, and thereafter the toils of the 2010s? Because Woods changed swing, seeking longevity, as even to the naked, untutored eye it was obvious no-one striking that ball with such torque inflicted on the back muscles was going to last for long.

The late, great Bob Torrance – a master of swing mechanics – often opined at that time that Woods was as great as he had seen, but was storing up back problems for the future if he continued to swing the club like that. Bob was right, of course.

The other one in my estimation was absolutely right about Woods was the venerable US writer Dan Jenkins who, when asked what would stop Woods’ dominance around the time of the Tiger Slam, said: “A bad injury, or a bad marriage.”

The old man was right twice.