The Duel In The Sun is almost golf’s golden age now – the closest football comparison would be Mexico 1970.

For two glorious days in 1977, in vivid colour on TV and blazing sunshine at Turnberry, Tom Watson and Jack Nicklaus battled for 36 holes for a cumulative 19-under-par with Watson prevailing at the end of it, two 65s beating Jack’s 65 and 66.

The two best players in the world at the time left the 18th green at the end with their arms around each other’s shoulders, and the Duel went into legend.

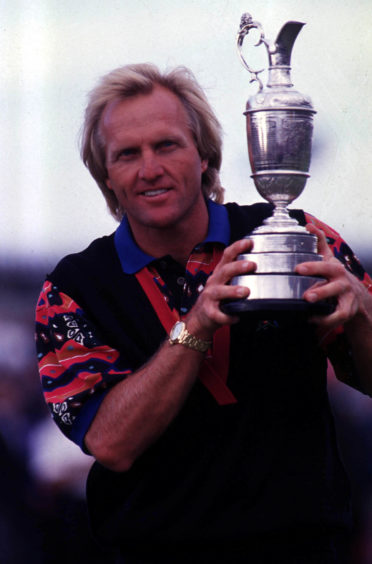

We should have had a second Duel 13 years later, in the 1990 Open on the game’s greatest stage, the Old Course, and again between the two best players in the world at the time. Unfortunately, one of them was Greg Norman, and it was a dispiriting flop.

What’s mostly remembered now about 1990 is Faldo’s coast to victory on Sunday with a record 20-under aggregate, the crowd around the Valley of Sin watching him hole out, the Red Arrows buzzing the R&A clubhouse in celebration and the Englishman crowned as the best player in the world. It should have been even better than that.

Norman was the World No 1 coming into the championship – and was to remain so until September – even though he had won just one major, his Open victory at Turnberry in 1986. The Australian’s domination of the PGA Tour was the reason he was No 1, but not for the first or last time the world rankings didn’t compute with widespread public opinion.

That had been best summarised by Jack Nicklaus a year before.

“Right now, he’s `The Man’ ,” said Nicklaus, who had himself been `The Man’ for a long time.

“He’s the guy, when he comes into the locker room, the others say, that’s the guy we have to beat”.

Nicklaus was referring to Faldo, and in the 18 months previously the relentlessly driven Englishman had won back-to-back Masters, an Open title in 1987, and had four top fives in the majors.

Faldo came to St Andrews in 1990 armed with that record, and with a couple of secret weapons.

One was a two-wood, a club now obsoleted by modern technology, and not a regular in Faldo’s bag even then. “A good links course club” he said, the lower flight working the winds and the contours of the Old Course better off the tee than his driver.

Faldo’s other secret weapon was “the blueprint”, a sheaf of detailed notes on how to play the Old Course gifted to him by fellow Englishman Gerald Micklem, a former captain and champions committee chair at the R&A who had played and set up the Old Course so often that he was probably the leading non-St Andrian authority on it.

Still, Norman was far from a novice at links golf and St Andrews. He’d learned the links from experience and from Peter Thomson, not far off Micklem as a “foreign” authority on the Old Course.

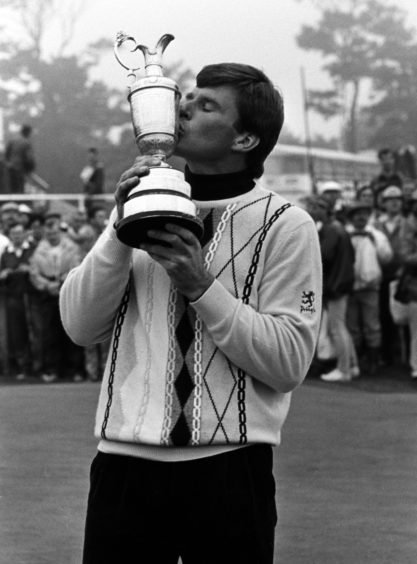

Norman’s win at Turnberry in 1986 included the 63 in the second round in a whirling storm, possibly the greatest single Open round in history. He’d come agonisingly close to a second Claret Jug the previous year at Troon, losing a play-off to Mark Calcavecchia after a thrilling charge in the final round.

Aided by holing out from the 18th fairway for eagle in the first round, Faldo was one shot behind Norman’s peerless opening 66. On the Friday, Faldo made up the deficit with a 65, as Norman’s 66 had the hole-out eagle – a 75-yard wedge third shot to the long 14th which spun back into the cup.

It was all set up perfectly. The pair were at 12-under – a record for 36 holes at the time – four shots ahead of Craig Parry and Payne Stewart.

Despite being in different pairings, they’d been duelling already, as Faldo said – “We seemed to be chasing one another. As soon as one birdie went up on the board, another went up.”

Norman concurred. “Faldo and I grew up together playing in Europe and have been matching shots since 1977,” he said. “This should be interesting, to say the least.”

The weather was perfect, like 1977, just a stiffer breeze in the late Saturday afternoon coming on with the tide.

This writer, covering only his second Open – I’d followed every shot of Norman’s final round 64 the year before – raced to the course early on Saturday in expectation of witnessing a classic.

Little in the 30 years since has let me down so badly. Tom Watson at Turnberry in 2009, or maybe Scotland’s first match at the last Rugby World Cup. But nothing else.

Norman horseshoed the cup at the second and three-putted, setting the tone for his day. Two more short putts went astray on the front nine, and he drove into bunkers on the 12th and 13th, taking the almost inevitable extra stroke at each hole for both of them.

Faldo also drove into gorse at 12 but hacked out sideways, wedged to eight feet and made the putt. It was his only wobble, save for a regulation five at the 17th. Norman lurched to a 76, and plummeted down the leaderboard; Faldo would have another Australian, Ian Baker-Finch, for company in the final round after his 67.

The final round was a procession but the winner remained with his other-worldly focus. Faldo was friends with Baker-Finch, but their only exchange during the final round, according to the Australian, was on the third when Baker-Finch had said “Nice shot” and Faldo replied “Yeah”.

Towards the end on Saturday, Norman turned to his caddie Steve Williams and said, “I guess, Steve, sometimes it’s better to be lucky than good.”

Williams, who was later to work Tiger Woods’ two Open wins at St Andrews, remembers that as being the time he realised he needed a new bag.

Naturally, you’re drawn to another hindsight that the duo’s scores on that Open Saturday were exactly the same as they were during Norman’s most famous and final disaster, at the 1996 Masters.

Then, the Australian saw a six-shot lead evaporate, and it was the coup de grace of his extraordinary list of disasters in major championships.

But again, like the world rankings, something doesn’t quite compute.

Norman was brilliant winning in 1986, and right between the 1990 and 1996 meltdowns, at Sandwich in 1993, he won a second Jug with a faultless final round 63 from the front pursued by the world’s best at the time, including a charging Faldo. If Norman was so fragile mentally as is often claimed now, wouldn’t he have lost those as well?

Norman today is as rich as Croesus, was one of the best ball-strikers in history, and has two Claret Jugs. Would a Green Jacket and one or two more majors have made him immeasurably more content with his life? A little bit maybe, but not a lot.

He lost a lot more than he won, but then again, that’s true of all of us.