Award-winning St Andrews golf historian Roger McStravick was no stranger to the chaos of conflict when growing up in Lurgan, Northern Ireland, during ‘The Troubles’ of the 1980s.

His golf clubhouse was blown up by terrorists three times.

A sniper shot a fellow golfer in the head on the ninth green as Roger stood just 150 yards away, waiting for him to finish putting.

The victim, who worked part time with the Royal Ulster Constabulary, only survived because he turned his head at the last moment. The bullet passed through his cheek instead of his skull.

But what was it about golf that helped overcome conflict, and how does that unifying power inspire Roger to celebrate golf history in St Andrews today?

“The great thing about Lurgan Golf Club to this day is that golf is the religion,” says Roger.

“All my best friends were Catholics and Protestants. Golf brought us together.

“It was policy that if anyone tries to bring up religion in the club house they are warned and then asked to leave. But golf does that. Golf is the great leveller. And that’s the same in St Andrews today as it is anywhere.”

Celebrating the ‘forgotten’ born and bred St Andrews golf champions

Today, Roger, 53, finds himself in the much quieter world of St Andrews, the Home of Golf.

Living near St Andrews with his NHS psychologist wife and two young children who attend Strathkinness Primary, Roger has become an accomplished golf historian and author.

But at the heart of his work, there also lies a desire to celebrate the “forgotten” 19th century champions who were born and bred in St Andrews at a time when the game and the town were much simpler than today.

Walking with Roger in St Andrews, his passion is evident as he points out landmarks and offers stories about the golf greats who once lived there.

“On the corner of Golf Place and The Links, there’s Allan Villa, the home of Allan Robertson,” he says, his voice full of reverence for the man he calls the “king of golf” before Tom Morris’s rise to fame.

“And then round the corner at 1 Albany Place is where Tommy Morris lived.

“There his wife and young child died, stillborn. I recently got a tour of the house and it was very emotional.

“I could almost imagine how events played out there in September 1875.”

Tommy, already a four-time Open champion, just like his father Tom Morris, died just three months later aged just 24.

Roger is in no doubt that if Tommy had lived, he would have gone on to win the Open a record number of times.

Erection of St Andrews gravestone, statue and plaques

Much of Roger’s work centres on reclaiming these “lost” stories.

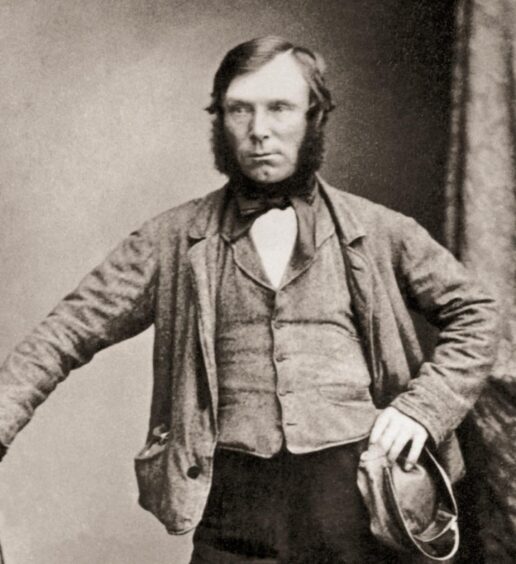

In 2018, he spearheaded a successful campaign to erect a gravestone for Jamie Anderson.

He was the 19th century professional golfer from St Andrews who won the Open Championship three times yet died destitute in the Thornton Poorhouse before being buried in an unmarked grave in the grounds of St Andrews Cathedral.

Roger was also part of a team led by Commodore Ronald Sandford that erected a statue of ‘Old’ Tom Morris at the Bow Butts last year, created by Fife sculptor David Annand.

It was unveiled by Tom Morris’ great great granddaughter Sheila Walker, assisted by former Open champion Sandy Lyle.

Thanks to the St Andrews Pilgrim Foundation, blue plaques will soon be erected for Allan Robertson at Allan Villa, for Tommy Morris at 1 Albany Place and for Jamie Anderson at 9 The Links.

“These champions shaped the game as we know it,” Roger says. “It’s important to remember them.”

How did Roger McStravick become an award-winning St Andrews golf historian?

Roger started playing golf at the age of 11, pestering his parents for a set of Lee Trevino clubs for his birthday. He quickly excelled. Yet his passion for golf history is not something that appeared overnight.

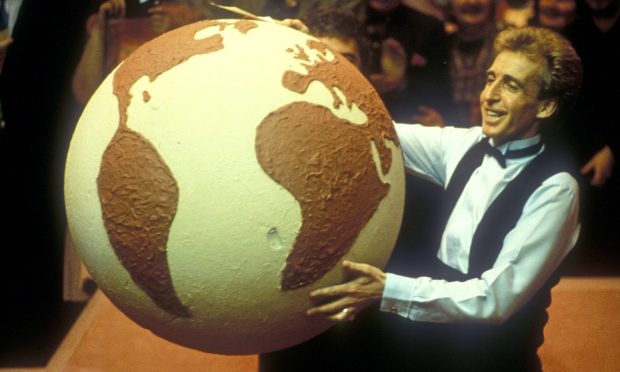

Starting his career in London as a music industry booker, he looked after big names like Van Morrison, Bryan Adams and Midge Ure.

Then in 2001, he made the bold decision to leave London and pursue a Masters in golf course architecture in Edinburgh.

From there, he worked in golf PR for VisitScotland, and then in PR for the Fairmont, outside St Andrews.

Attending an event featuring Peter Allis at the Byre Theatre during the Open Championship of 2010, he was massively inspired by the work of local historian David Joy depicting ‘Old’ Tom Morris and has owed a debt of gratitude to him ever since.

Today, Roger, who is a member of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club with a handicap of seven, immerses himself in the town’s rich golfing history.

He is a double winner of the USGA’s Herbert Warren Wind Book Award and the British Golf Collectors Society Murdoch Medal for his books St Andrews – The Road War Papers and St Andrews In the Footsteps of Old Tom Morris.

But one of the most significant of these projects is his new book: Allan Robertson of St Andrews – The King of Clubs 1815-1859.

What inspired Roger McStravick’s new book about Allan Robertson?

A devout Tom Morris fan, it was not his plan to write a book on Robertson.

But when he was persuaded to pick up the project following the untimely death of golf historian Bill Williams who started it, his immersion over the past four years could not be more rewarding.

“My impression of Allan Robertson before that was quite negative,” he says.

“He was never the hero. He was a bit pawky, oh and he was a caddie. But that’s a million miles away from who he really was – he was a businessman, employer, designer of golf courses.”

The story of Allan Robertson, a St Andrews ballmaker considered the top golfer of his era, was overshadowed by Tom Morris, whose rise to prominence in the mid-19th century coincided with golf’s explosive growth.

“When Allan died in 1859, Tom became the ‘go to guy,’” Roger explains.

“From that point on, Tom Morris became the face of golf. But people forget that before Tom, Allan was the best. His father was champion golfer for five years.

“The Robertsons, his family, held the title of champion golfer for 24 of 30 years. The Open Championship came about as a result of Robertson’s death. That legacy is incredible.”

Aiming to correct an ‘historical oversight’

During research, Roger found himself transported back to 19th century St Andrews, a time when the town and the coastline looked vastly different from how they appear today.

The original layout of the Old Course, for example, had 22 holes, with the 18th green located much further from the current location.

Before construction of the Bruce Embankment, the sea lapped where the first fairway of the Old Course is today, prompting modern debate about coastal erosion.

Robertson’s tenure coincided with Hugh Lyon Playfair’s redevelopment of St Andrews streets into something like what is known today after centuries of post-Reformation decline.

Roger is determined to ensure that the contributions of the “forgotten” golfers of the 19th century are not lost to history.

But he feels especially “blessed” that he is able to do this in St Andrews where the archives are “incredible” and layers of history can be found at every turn.

Conversation