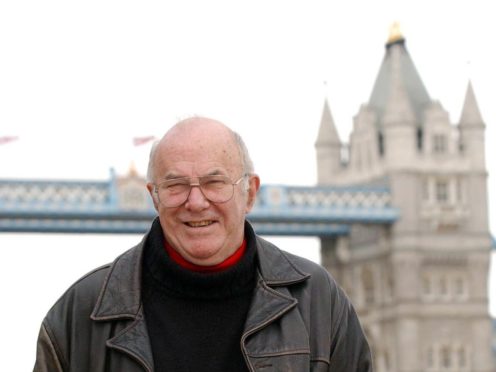

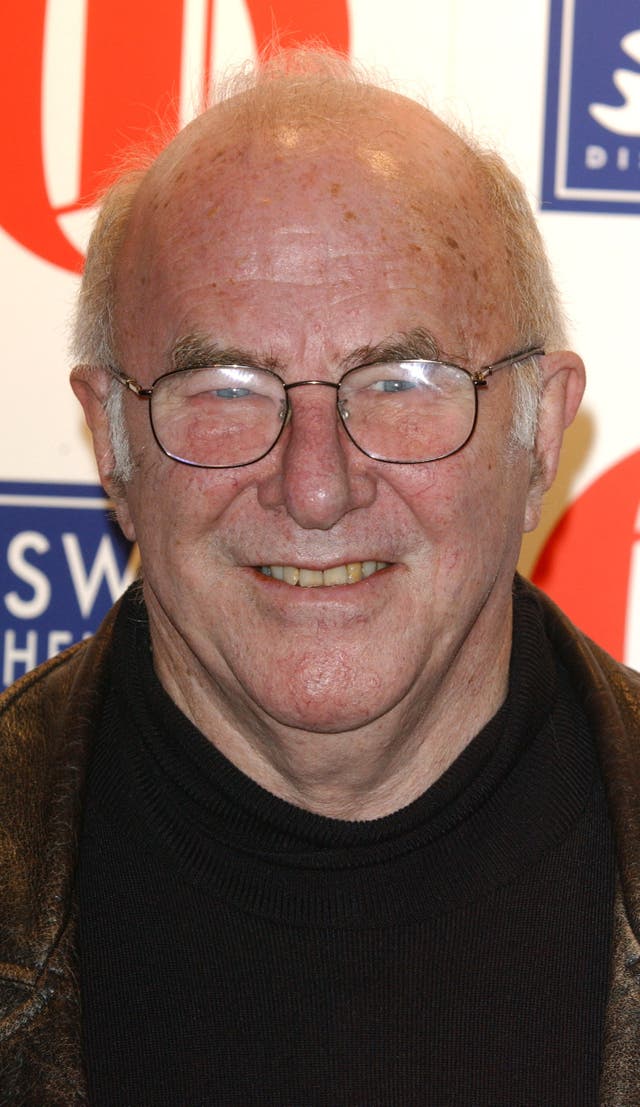

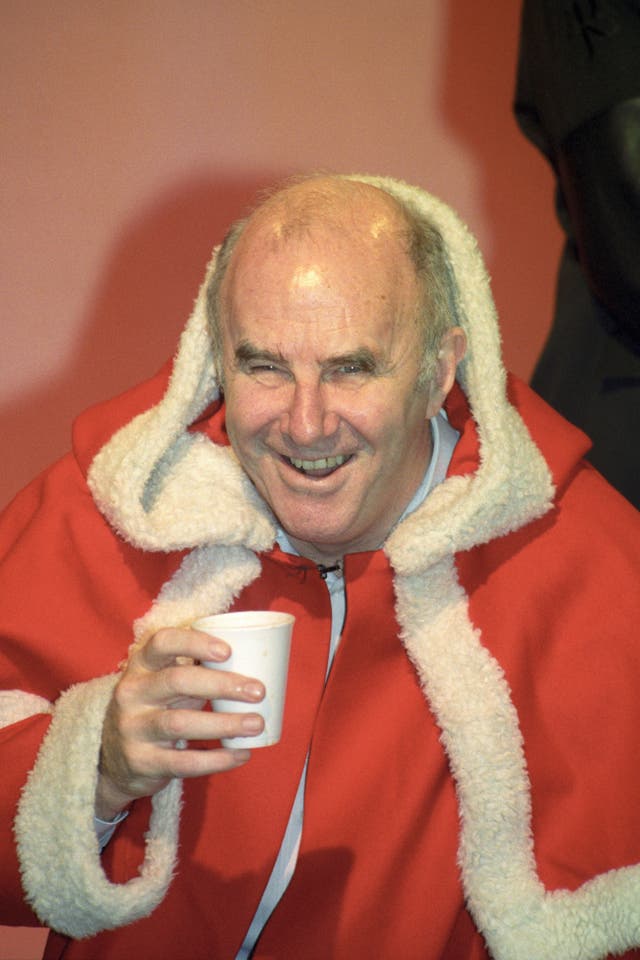

There was no limit to the talents of Clive James. The avuncular Australian was equally at ease presenting prime time TV shows and penning poetry for literary journals.

The celebrated broadcaster and writer, who has died at the age of 80 a decade after being diagnosed with leukaemia, wrote more than 30 books.

So it is no surprise he even found the time to write his own obituary.

He put a brief biography on his website years ago saying it would “serve as a cheaper obituary than anything most newspapers are likely to have in the freezer”.

He also warned journalists to keep “in mind that shorter is better, and that a single line is best”.

It was typical of the man who never stopped writing and never stopped joking.

One joke that was on him was that despite his considerable literary prowess, he will probably be best remembered by many as the man who introduced the unique world of Japanese TV – and in particular the painful challenges of the game show Endurance – to the UK.

Clips from Endurance, which regularly left its contestants rolling around on the floor screaming in agony, featured in the long-running Clive James On Television, which saw him put some the world’s most bizarre programmes under the spotlight.

The hit TV show , with James’s wise-cracking presenting style, was a natural move from his days as the television critic for The Observer, where he did his best to transform the TV review into an art form.

There were moments of unhappiness and even tragedy behind the laughter – he wrote movingly about the death of his father, who survived years in a Japanese prisoner of war camp only to die on his way home to Australia when his plane crashed.

And his long marriage to the scholar Prue Shaw struggled to survive when it was revealed he had been having an affair for several years.

For a man who presented his own chat show, a series of successful travel documentaries and a look at Fame In The Twentieth Century, James himself never seemed that interested in being a celebrity.

The world only learned of his illness in May 2011 – at which point he had been ill for 15 months – when he wrote to The Australian Literary Review to explain why he could not write for them.

Born on October 7, 1939 in Sydney, James was educated there before making his way into journalism and then moving to England in 1961, where he studied at Cambridge University and worked on Fleet Street.

He was part of a generation of Australian expats including Germaine Greer and Robert Hughes, who lit up the London literary scene.

James never stopped writing. There were books of poetry – with the first, Peregrine Prykke’s Pilgrimage, appearing in 1974. They were joined by best-selling memoirs, novels, essays and even lyrics for a series of albums with musician Pete Atkin.

Towards the end of his life, he regretted being unable to travel back to his native Australia because of the nature of his illness but never complained, telling one interviewer: “By complaining at all I am complaining too much. We are all lucky to have got here.”

In October 2015, James admitted feeling “embarrassment” at still being alive, a year after predicting his imminent death from cancer.

In a column for the Guardian, he said he had written himself “into a corner” by announcing a year earlier that he would die very shortly, when in fact his health rallied thanks to an experimental drug treatment.

A new chemotherapy medication prescribed to the writer was “holding back the lurgy”, he wrote, “leaving me stuck with the embarrassment of still being alive”.

But he soon turned his illness into another subject of his tongue-in-cheek humour as he continued to write entertaining pieces about the latest developments in his health.

Another Guardian comment in 2017 saw him share with readers the day he received his first wheelchair, which he described as a “super-duper semi-Ferrari,” a “thing of beauty and precision” before he decided to practice whizzing around his house in it.

In the same year he also announced plans for a sequel to his 2015 poetry collection Sentenced To Life, which he had intended to be his last.

Injury Time marked a positive turnaround in his view of his own mortality, and he said at the time: “I felt like I’d dodged a bullet, and when you’re dodging a bullet the best thing you can do is turn it into a dance.

“This is a very different book … the new drugs are working and the danger now is that I’ll bore everyone to death.”

In one of his last television appearances James was interviewed by Mary Beard in a special episode of Front Row Late.

The 30-minute exchange in his Cambridge study, stitched together from a longer, more halting conversation, laid bare the extent of his illness when it aired on BBC Two.

Despite his physical state, James released an epic poem in October 2018, titled The River In The Sky.

Meditating on the ever-dwindling length of such works of literature, he wrote in the Guardian that epic poems will always exist “because every human life contains one”.

The River In The Sky concludes: “Books are the anchors, Left by the ships that rot away. The mud, The anchors lie in is one’s recollection, Of what life was, and never, late or soon, Will be again.”