From an early age I was party to conversations about the struggle against apartheid that Nelson Mandela later came to represent.

That gave me the chance to make a judgment about the destructive wastefulness of a system that refused to allow the majority of its people to attain their full potential.

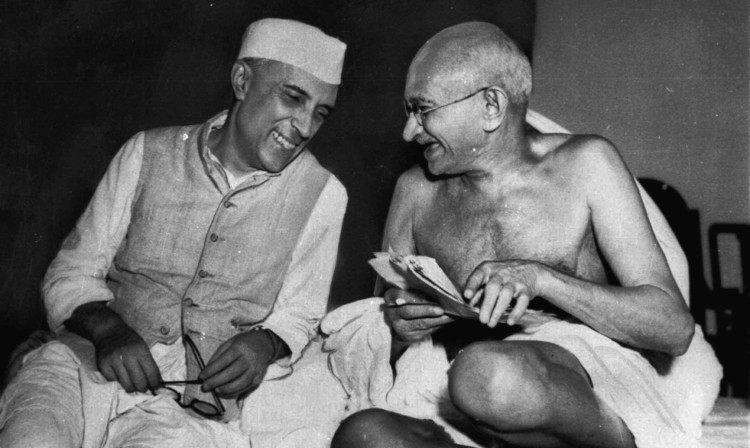

I learned too, about how, decades before Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent campaign had inspired Indians to seek independence.

Gandhi was a political magician. He knew a small, armed force could not contain the ambition of millions of Indians. He was also a dazzling PR man who used his cult status to embarrass and cajole those in power.

He had a few odd ways of testing his personal resolve, though.

But to me he has remained an inspiration.

Given Gandhi’s own use of image to achieve his aims, I never considered parody irreverent.

So during that period in your 30s when every social gathering seems to be a fancydress party, I always suggested going as Gandhi.

A horrified Mrs Ferguson overruled me each time and invariably I went as Bob Marley.

All that changed one snowy Friday just before Christmas one year. I dashed in from work to get ready for another party to discover Mrs Ferguson ill in bed.

She told me I would have to go alone.

That is when the spirit of rebellion stirred.

A few snips at a sheet, a razor over my head, glasses, sandals, my grandfather’s walking staff and I was Mahatma Gandhi at last all unseen by Mrs Ferguson.

Given the weather, I felt a taxi might be in order but I was told to take the Tay Rider bus ticket and change buses in the town.

At the bus stop, old Mrs Mitchell appeared through the blizzard. “If you’re going to Tesco, could you help me home with some wicker baskets,” she asked. I said I wasn’t going to Tesco.

“Are you going to Morrison’s then?” She looked surprised when I told her I was going to a party.

After two bus trips I reached the venue as the weather turned nastier.

I bounded in and time seemed to stop.

It was a Christmas party not a fancy dress party. There were gasps and shrieks of, oh my godfathers, as I was gently ushered out.

The walk back into town was not without incident. Some ruffians outside a chip shop tugged at my sheet and that led to a misunderstanding

with girls leaving a dance class.

But I can still run like the wind and with God’s speed I made it to the safety of the number 43 bus where old Mrs Mitchell was sitting with her wicker baskets. “So you did go to Morrison’s?” “Yes,” I replied.

I helped her home with the baskets and as she brewed weak coffee, Mr Mitchell cracked open tales of the sea.

When I was leaving, Mr Mitchell said I reminded him of someone he couldn’t place.

By the time I reached the end of the path, he had remembered. “Pandit Nehru”, he shouted.