The Ripper’s shadow of terror held late 19th century Britain in fear and awe.

While London’s East End was punctuated by the regularity of his atrocities, the rest of the nation felt echoes of insecurity and mistrust.

Britain was gripped by Ripper hysteria and newspapers satisfied the public mood.

The coverage given to Ripper reports from any part of the country was unparalleled.

After all, Jack was an invisible killer and the belief was he could strike anywhere and at any moment.

Ripper notoriety also proved seductive for attention seekers and mischief makers.

A mob even formed in Kirkcaldy to drive a Ripper suspect to ground and police in Elgin received a report that Jack had moved north in his lust for “purer blood”.

The last man to be hanged in Dundee, William Henry Bury, had his moment as a Whitechapel suspect but he was quickly ruled out. However, that legend lives on.

My colleague, Graeme Ogston, touched on Bury’s case when he reported on a ceremony to mark the end of high court sittings in Dundee.

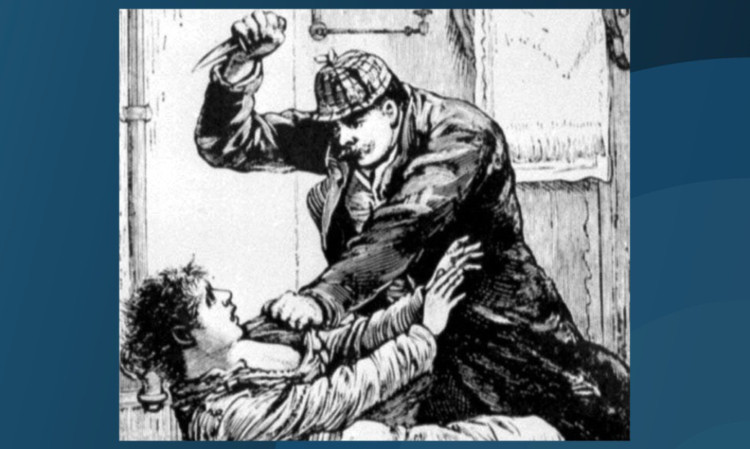

Bury (30) was a drink-sodden chancer who married a London girl, Ellen Elliot, with a bit of money. He charmed her family but brutalised her.

It seems he invented a job offer in Dundee and the pair sailed north in January 1889. They lodged with a Mrs Robertson in Union Street for nine days before he blagged a basement flat at 112 Princes Street.

During the fortnight they lived there, Bury propped up bars boasting of his money.

On Sunday, February 11, he presented at the police office to report his wife’s death. He told a Lieutentant Parr that he found his wife dead with a rope around here neck the Monday or Tuesday before. His response was to mutilate her body with a knife, break her legs and crush her body into a box.

Police found Ripper messages chalked on his door but Dundee and London police dismissed him as a fantasist.

His trial lasted 13 hours before the jury returned with an ambiguous verdict. They found him guilty but recommended mercy because of conflicting medical evidence.

The judge, Lord Young, was having none of it and told them to bring back another verdict. They duly delivered a unanimous death sentence.

Bury’s agent, Mr P.J. Tweedie, petitioned the Secretary of State because the jury had in fact delivered a not-proven verdict.

Rippermania surfaced in Kirkcaldy in September that year. A mob accused a stranger of being the killer. He fled to the police office where a crowd rippled with rumours that he had given himself up.

It turns out the man was a commercial traveller. His long beard persuaded locals of his guilt.

Within days, the Ripper circus moved to Elgin where police received a letter warning he was hunting for prostitutes.

Similar hoaxes and even self-mutilation were reported across the country but still Jack remained at large.