In June 1940, following the collapse of France and the piecemeal repatriation of the greater part of the British Expeditionary Force, Prime Minister Winston Churchill addressed the free world.

He prepared nation, empire and potential allies for the battle to come.

Mr Churchill spelt out two possible futures to his radio audience. Broad, sunlit uplands or the abyss of a new dark age.

He warned a dark age of evil would be made more protracted by the lights of perverted science….the lights of perverted science? Churchill must have been aware that the Nazi empire was becoming the cradle of technological and scientific atrocities.

The objective of Nazi science had become destruction. Annihilation had become the Nazi thesis. And the antithesis was a matching science race in the West. The synthesis of these opposing positions led to a shift from a mechanical age to a technological age. The birth pangs of our modern world were being sensed in those days of gloom.

The demands of war led to the mass commercialisation of nylon, first introduced in 1938 in toothbrushes. As war raged, it was used a silk substitute in parachutes and hosiery.

As peace was won, the sunlit uplands did appear but the legacy of perverted science’s lights did not dim completely.

Our need to attack and defend left us with the jet engine, the computer and the genesis of the space race, among dozens of other inventions and developments.

Six years of total war also bequeathed us with the means to manufacture industrial quantities of nylon, a product that served its purpose with distinction in our time of need but one that, in peacetime, was given over to sinister functions.

None was more sinister, more reminiscent of the abyss or perverted science than the nylon shirt.

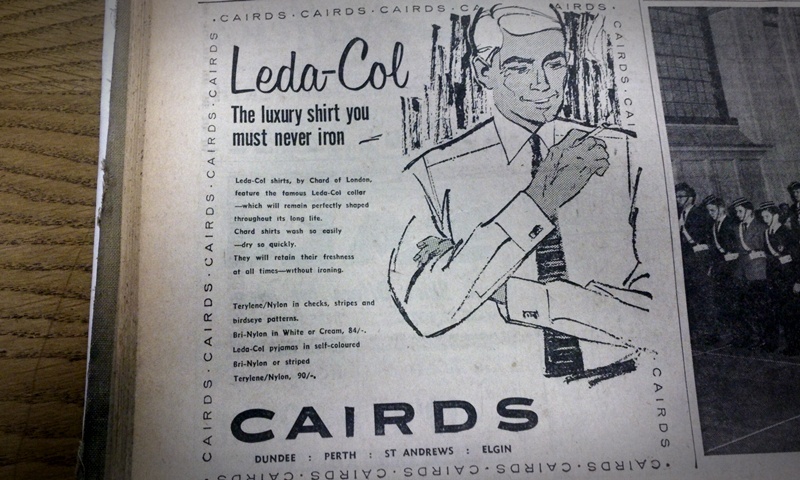

I came across an advert for this abominable trend in a 1963 issue of The Courier when its peddling by manufacturers and retailers was slammed into top gear.

The construction of the advert is telling. Below the trade name, Leda-Col, is a bold sub heading stating: “The luxury shirt you must never iron”. I would place an emphasis on MUST. Contact with an iron, even on the coolest setting, would see the shirt shrivel like a crisp bag at a furnace door. Contact with any heat source was an alarming gamble.

I’m surprised the advert, which shows a man smoking a cigarette, did not carry a health warning not warning of the dangers of tobacco but warning of the peril of a naked flame being in the same room as a nylon shirt.

Anyone who ever experienced the discomfort of wearing a nylon shirt will recall the horror of it climbing up your back like a caterpillar, the crackle of static electricity, its mendacious caress against the skin and its inability to retain any heat. In fact, nylon shirts seemed to amplify the cold so much you would have been warmer walking about shirtless in the face of a relentless easterly wind.

But what floored me when studying this advert was the price of this garment. It started at 84 shillings, I think that is £4.20. Run it through an inflation calculator and it would have set you back the equivalent of £74 in today’s money.

For £4.50 (£81.05) you could buy nylon pyjamas. We now look back at nylon pyjamas with terror. But that is because we now know what was to come to the market next nylon sheets, bringing the experience of the complete absence of friction to the British bedroom for the very first time.

It is a wonder climbing into bed was not made into an Olympic sport in the 1960s.

* As an aside, at some point I will be doing a comparison of the real cost of goods now and in the past and another advert from 50 years ago that caught my eye was one for a Cine camera from Elena Mae at £27 and 18 shillings or £502 once inflation is calculated. More on that in the future.