The big pant revolt was as volcanic as it was elastic.

A bottom-up movement that expanded to engulf a town.Sudden as the Arab Spring, it was as brief as Ceausescu’s demise.

It was the perfect revolution. Planned to precision, executed with determination, it produced a number of happy ends.

It was sparked when comfortably sized ladies of a certain age were pushed beyond the threshold of tolerance.

The disappearance of traditional High Street retailers had already forced them to change their shopping habits.

But when East Angus Co-op closed its Arbroath department store, simmering unrest gave way to public protest.

The store was the only place in Arbroath to sell underpants in waist sizes about 52”.

The most common requirement among the ladies was 66” so they faced trips to Montrose or Forfar where big pant dealers remained.

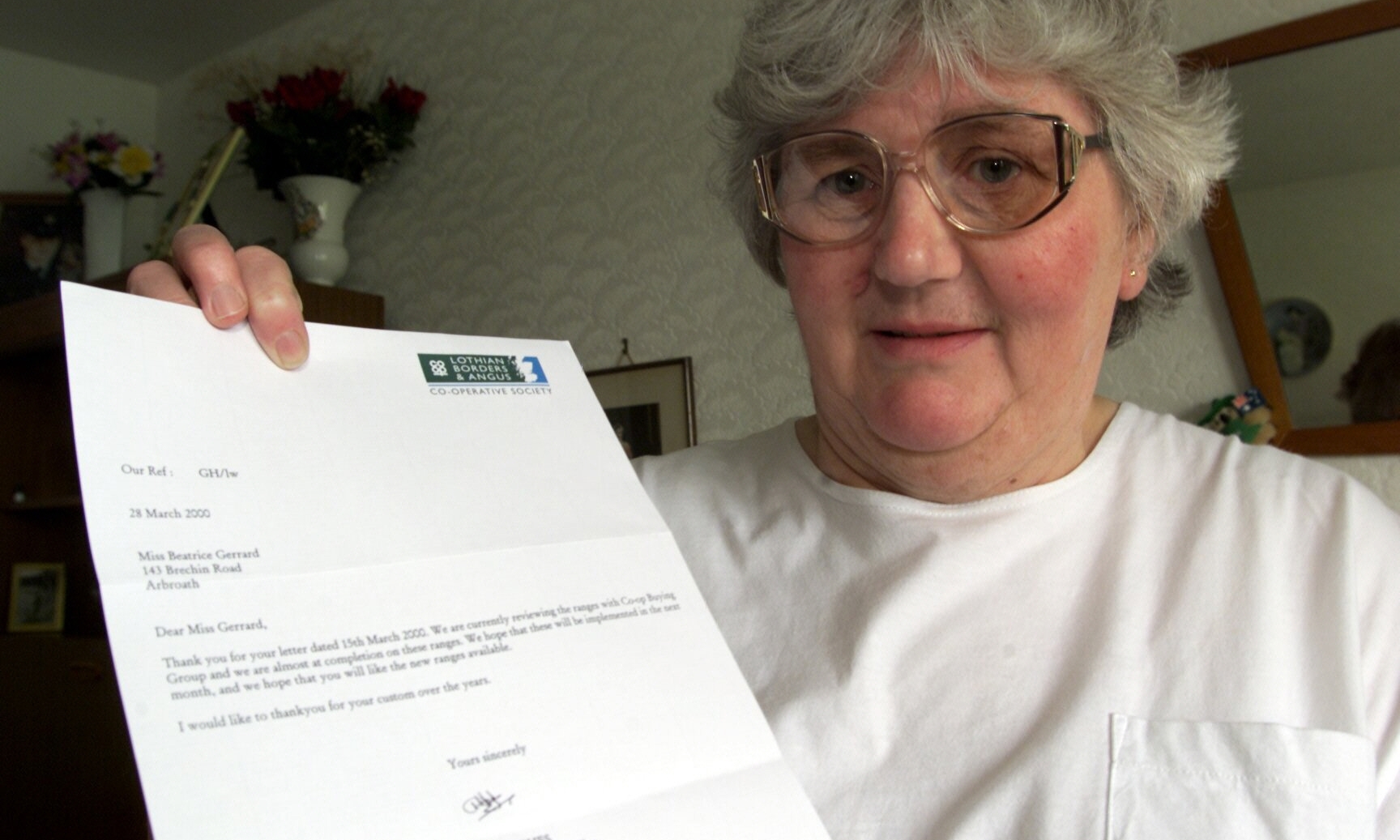

I got wind of the uprising in a late-night call I took from Beatrice Gerrard.

You’d better come quickly. The mood is getting ugly, she told me.

When you are a news reporter, it is useful to have extra pairs of eyes and ears in the community. Beatrice came with a dozen pairs of each so I knew it was serious.

We published their grievances and Beatrice was game enough to pose for a photograph holding a pair of the pants.

And within a matter of days, a solution was found. An angel in stretch cotton appeared on the scene. This was a woman who operated a little-known dial-a-pant service.

The Arbroath ladies were thrilled. She did home visits and fittings and could source anything they needed.

The revolt was a victory for community spirit and self reliance.

Beatrice had identified a real problem facing a large section of the community and had acted on their behalf.

With the closure of the department store, elderly women could not get the clothes they needed. Some of them lacked mobility and could not make the trip to Montrose or Forfar.

Beatrice knew that publicity could shine a light on the problem so took the big pant line which she knew the press would go for.

She and thousands like her in communities across the land are examples of people who believe they can make a difference and are prepared to put their heads above the parapet.

Grassroots political activists are another example. Not a lot of glory chapping doors for a party on a wet night but they do it because they believe their philosophy can help build a better society.

The same goes for many of the hundreds of elected politicians I have worked with over the years. A great deal of their time is taken up with housing complaints, road and street lighting problems.

Then there are the churches in Angus whose response to the devastation of drug addiction has not been to retreat and pray but to retreat, pray and take action, to work with the stricken families, send them to rehab and establish premises to support them.

There are those toil hard throughout the winter to organise summer events that bring people together. We don’t see the full extent of their labours but we know that communities would be harder, grimmer places without them.

Then there are those individuals whose willingness to challenge authority can bring about fresh ways of thinking and benefit the greater good.

One contact of mine objected to a council proposal to split a piece of brownfield land between home owners to extend their gardens. The council just wanted rid of the land.

But this man believed that it was public ground and it should be offered for sale. The council relented in the end and invited bids. My contact did not want the land but felt obliged to bid a pittance.

To his amazement he was the only bidder and bought it. He then applied for planning permission for two houses but was turned down. Over many years he battled with the council and eventually a Scottish Government reporter not only upheld his appeal but recommended that

the site could accommodate 22 houses, including low-cost homes, and contribute significantly to urban regeneration.

If he had been unwilling to take on the council, the land would have been enclosed as gardens and, eventually, homes would have been built on productive farmland.

You can encounter the rougher side of life in this job but that is tempered by the privilege of meeting those whose dedication and enthusiasm turn places where people live into communities.