SOUND BITES weren’t invented by 20th century spin doctors. The term might not have been familiar back in the day but that’s what they were. And like the ones we know and love or loathe today, they stick around to haunt future generations and arguments.

And who better, in Scotland’s history, to provide a literal sound bite set to music as a popular song than Robert Burns? “We’re bought and sold for English gold; such a parcel of rogues in a nation.” Stirring, angry words full of, as Burns says elsewhere in the same poem, pith and power.

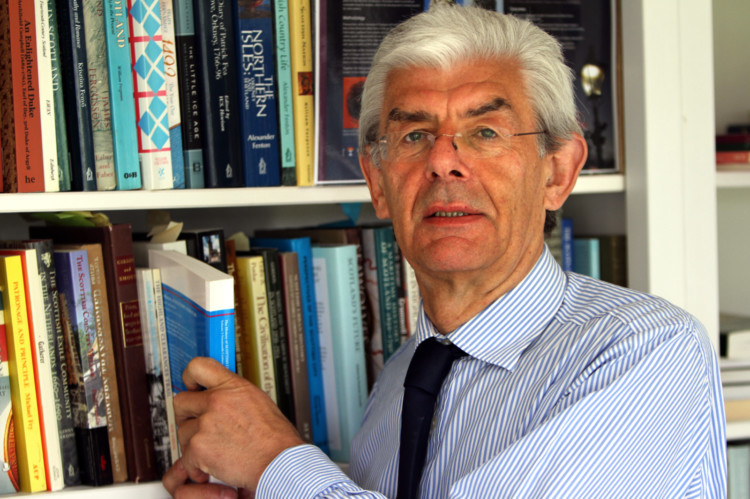

Seven years ago, Professor Christopher Whatley’s prize-winning book The Scots and the Union took that image apart and challenged the received wisdom of the nation being sold down the river to bullying English authorities for the benefit of a small number of venal Scots. Then and Now is a refreshed and extended version for a new context.

He wrote the original, he says, because: “There’s not much history in the current debate, unusual when you’re talking about national independence movements; perhaps because history doesn’t always coincide with the political points being made eg. that the Scots are currently in a relationship they didn’t want to be in.”

Further research from personal accounts, memoirs and diaries underlines the fact that there was as much debate then as now and that there were many “don’t knows” alongside those with an axe to grind. The book also notes that the terms on which the Union was negotiated were very clear and detailed, down to individual amounts of tax and customs rates.

“Money did change hands undoubtedly but many who had a say were already pro-Union for religious and wider economic reasons the maintenance of constitutional monarchy and the Protestant succession for example, in the face of Jacobite threats and the aggressive France of Louis XIV,” Professor Whatley continues.

“The Scots negotiators also got a very good deal on the share of the English national debt, the currency and compensation on the disastrous Darien scheme that had led to financial ruin for many in Scotland.

“Subsequent to the first edition of the book, we discovered that opponents of the Union, the Country Party led by the Duke of Hamilton, had received funds from the Vatican, channelled through France. If they had won and the Union hadn’t gone through, would the other side have been singing: ‘We’re bought and sold for Vatican gold?’

“It’s dangerous to look back for heroes.”

All cliches have their roots somewhere in truth and Professor Whatley sees the “canny” Scot dominating the decision making process 300 hundred years ago and today. He posits that what we are currently experiencing is a debate about effective government. Drawing comparison with the Baltic States, he reckons: “The Scots have always been a nation with a strong sense of a distinctive cultural entity but we haven’t been oppressed in the way that many other peoples fighting for their independence have been. Scots symbols and icons have rarely been successfully suppressed and in fact, have often flourished.”

He has equated the current position to being in bed with a teddy bear rather than an elephant. But the current elephant in the room may well be that what is being presented as effective government, north and south of the border, is two very different models.

“I think many now feel that Westminster as it stands is no longer fit for purpose and the Union is vulnerable. Its original aims really no longer exist the religious aspects, we take constitutional monarchy for granted, we are not an under-developed economy and we have no directly aggressive neighbours, although cyber threats, food security and a fast-changing world the Russian bear is growling again give pause for thought. So what is it for and why is it still there?

“In 1707, if the people on the streets had had a vote, they would probably have gone for a separate parliament under a single monarch, a more powerful, devolved Scottish parliament and I’m not sure this isn’t the default position of Scots today. If we were able, across the country, to write the future, I suspect we would end up with a federal Britain, with more regional assemblies with a broader framework.”

Many would argue, of course, that political point-scoring and grand-standing on both sides has dominated the current debate and that the finer points and actual terms will only surface in any meaningful way after the votes and the die are cast. People may vote for what they know but still won’t get the unchanged status quo as it currently stands you can’t after all, put the genie back in the bottle. Even those passionately opposed to independence actively or implicitly concede that nothing will be the same again and are already talking about changes/offers/further devolution/extra powers etc for the future.

They say if you put two Scots in a room you’ll get at least three opinions. Professor Whatley added: “One of the exciting things about the present debate is that the political public meeting is far from dead it’s a living, breathing, kicking event and people are turning out to talk and argue in considerable numbers.”

And history and its lessons can play a vital part in that. “I’ve been called a Unionist historian but I’m not; I’m a historian of the Union. History doesn’t provide a clear route, history makes you think. And I don’t have the answers as a historian all I can do is get people to think about it.”

l Professor Chris Whatley is talking about his book and research on Thursday May 29 at 6pm in the Dalhousie Building of the University of Dundee as part of the university’s Five Millions Questions project. Register for free tickets on line or telephone 01382 381296.

l The updated edition of The Scots and the Union: Then and Now is available in paperback at £24.99 through Edinburgh University Press: ISBN 978 0 7486 8027 6