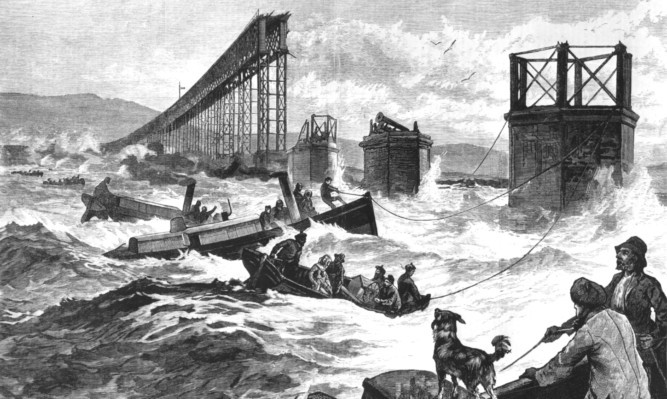

It is 135 years since the Tay Rail Bridge collapsed. Jack McKeown interviews historian Rosa Matheson, who has looked at the human cost of the disaster.

Harry Watts was not enjoying a pleasant end to his year. The diver had entered the inky blackness of the Tay, looking for bodies of the rail passengers who tumbled into the river when the Rail Bridge collapsed.

He immediately became tangled in the telegraph wires that had come down with the bridge. To add to his woes, the 53-year-old was wearing more than 40lb of lead weight, along with a stifling airtight helmet that was connected to the surface by an air pipe and communication line.

On top of that, it was icy cold and he had the famously powerful tide of the Tay to battle against. And then the sleeve of his suit tore open, filling with freezing water.

Day after day Watts who volunteered for the task and refused any pay crawled through the submerged wrecks of the train’s carriages. December 1879 ticked over into January 1880. By the eighth of the month 18 bodies had been recovered and when February arrived another 14 had been pulled out of the depths. Despite the endless, awful hours they spent underwater, only three of the recovered bodies were brought out by divers.

The Tay Bridge Disaster happened on the night of Sunday December 28, 1879. Initially, the North British Railway company said there had been 300 deaths and this news quickly spread around the world, with reports in newspapers as far away as Australia. Thankfully, railway employees had made a mistake and the actual death toll, although still horrendous, was much lower.

To this day, no one knows for sure exactly how many people died in the tragedy. The part of the Tay where the train sank is known for its strong tides and ever-changing sands. Forty bodies were recovered, at least 59 are known to have died and it is thought the death toll could be as high as 75.

Dr Rosa Matheson is a railway enthusiast. The Swindon resident’s latest book, Death, Dynamite and Disaster: A Grisly British Railway History, contains a chapter taking a fresh look at the Tay Bridge disaster, focusing on the lives of those who perished.

“I spoke to everyone I could who has studied, researched or published on the Tay Bridge disaster,” she says, “along with all the newspaper and magazine accounts, official reports, letters and other documents I could get my hands on. The death toll was initially estimated at 75 but research by many, including the Tay Valley History Society, seems to suggest it could be around 60 or 59.”

Nine of the dead were children. The youngest, Bella Neish, was just four years and nine months old. She was found on the beach at Wormit on January 27: the only casualty to be washed upriver of the collapsed bridge.

Some were found much further from the site of the accident the corpse of 43-year-old goods guard George McIntosh was washed ashore in Lunan Bay, 30 miles from the collapsed bridge.

Former Dundee councillor David Jobson was found near Newport. A well-off oil merchant, his widow could afford her own solicitor to fight the North British Railway and so received the greatest compensation of all the victims’ relatives more than £5,000 (around half a million pounds in today’s money).

“I got so involved in the lives of all these people who died that I would turn to my husband in tears,” Rosa says.

Her focus on the people who were found also reveals that there may have been time between the bridge collapsing and the train hitting the water for some of the passengers to begin planning their survival. One of the men, William Henry Beynon, was found without an overcoat and with his vest unbuttoned. A close family friend told rescuers Mr Beynon was an expert swimmer. At least two other male passengers were found without their coats on, as if they too had made themselves ready to swim for their lives.

“Some of them clearly knew what was about to happen,” Rosa continues. “But of course when the train hit the water and sank it would have been far too cold, dark and disorienting for anyone to stand a chance.”

The broken stumps of the first bridge still jut from the water under the shadow of the new rail crossing. At the end of last year, memorial stones commemorating the dead were placed in Wormit and Dundee. The 135 years old disaster still resonates today.

* Death, Dynamite and Disaster: A Grisly British Railway History is published by The History Press.