As 3D printers move from the realms of science fiction and closer to being everyday consumer devices, Jack McKeown visits Dundee University to see the technology in action.

A security alert was sparked in Manchester when police seized what they claimed were gun components created on a 3D printer. However, it now appears that police jumped the gun. The man arrested for allegedly printing sections of a firearm told police the parts were actually sections of the 3D printer.

Dundee University has a similar model of printer and research associate Grant Payne holds up the component that police claimed was the magazine. It does, indeed, appear to be part of the machine and not a component for a weapon. Early prototypes of 3D printed guns were inaccurate, low-powered and prone to failure. More recently, though, inventors in Europe and America have come up with more viable firearms. Anyone with a 3D printed gun would still have to buy bullets, however.

Despite concerns about the ability to create weaponry, there is no doubt the technology is fascinating, with a wealth of potential uses.

Already quite well developed, the cost of 3D printers has fallen enough to make them affordable to the hobbyist as well as businesses. The possibilities for the future are mind-boggling..embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; padding-top: 30px; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; height: auto; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }

The Courier visited Dundee University’s School of Engineering, Physics and Mathematics, which has half a dozen 3D printers, to learn more.

Grant (23) works on product and business development for the St Andrews Golf Company and also does research at the University of Dundee’s division of mechanical engineering. He shows us through to the research lab where several of the machines are whirring and clicking away.

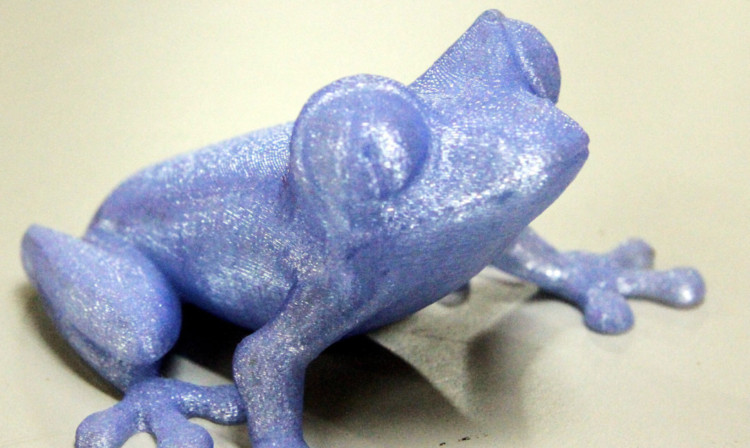

A variety of objects that have been created by the staff there sit on the table, including a putter head, traffic cones, some bones, a Dalek and even a crater from the dark side of the moon.

Holding up a 3D skull, Grant explains: “Some of them use ABS, which is a plastic. We have one that uses PLA, which is a bio-polymer made from corn starch.

“And we have a printer that uses a powder to create ceramic pieces.”

Prices range from the £1,750 MakerBot which can create objects up 28.3cm x 15.3cm x 15.5cm, through to more than £500,000 for machines that can 3D print metal. Basic 3D printers are limited to creating objects with angles of no more than 45 degrees.

Grant explains: “If you overlay one strand on top of the other you can’t have more than half of its width.”

More expensive 3D printers are able to build a support structure as they go along a sort of tiny scaffolding that is then removed once the piece hardens and sets. These allow almost any shape of object to be created.

Grant shows me the inlet manifold from an F1 car that was 3D printed. It still has a slight sheen of oil from use in a race car.

“3D printing allows you to print shapes that would be impossible or at least very difficult to cast using traditional means,” he says.

“It can also save companies millions in research and development costs. You can print a piece off and if it doesn’t fit or isn’t right you’ve only wasted a couple of quid.”

Dundee University’s head of physics, David McGloin, is spearheading a campaign to get a 3D printer into every school in the city with the view to having local companies fund the initial purchase of the machines.

Like many new technologies, the cutting edge of 3D printing design is not being driven by companies out to make a profit but by enthusiasts who want to showcase their creations. The charmingly titled website Thingiverse has a huge range of designs people can download and print off for free.

The site has everything from cufflinks and bangles to business card holders, miniatures of iconic buildings including the Taj Mahal and even the severed head of Justin Bieber.

Grant also has an app on his phone and tablet that allows him to take a 3D virtual design and use his screen to visualise it in the real world. Pointing his iPhone at the desk, a yellow tractor appears to float on top of the furniture. He rotates the piece of agricultural machinery through 360 degrees before enlarging it.

“You can use this to see what the object will look like before you even print it,” he explains.

In fact, the uses are limited only by your imagination.

Grant came up with an ingenious fix for a colleague’s car.

“My colleague drives an 80s Saab and the headlamp wiper had broken. It’s not easy or cheap to get parts so I scanned the old one and printed him off a new one. He spray painted it black and put it on his car. It works perfectly.”