During the First World War lives were lost in incredible numbers as thousands of Scots made the ultimate sacrifice.

It took a serviceman with a special kind of bravery, however, to volunteer for a role where life expectancy could be measured in mere hours.

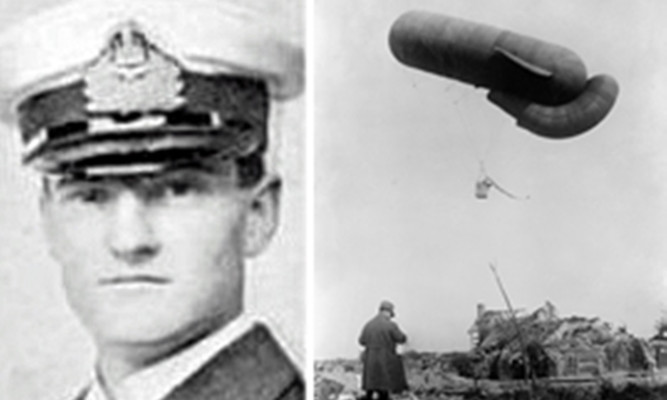

Such a man was Alastair Geddes, born in 1891 in Dundee, who was an adventurous and well-travelled early member of the Perth-based Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

As the centenary of the conflict is marked across the world, his sacrifice and those of others who fought and died will be acknowledged and remembered as part of Perth’s Doors Open Day events on Saturday.

His will be one of a number of tales told during a special First World War exhibition at the Fair Maid’s House Visitor Centre in the city.

After graduating from Edinburgh University in 1914, Geddes joined the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), before being posted to the Balloon Division, where he was swiftly promoted to the rank of major.

The role was highly dangerous, with a terrifying mortality rate.

The men of the corps were tasked with sitting in their balloons making aerial drawings or taking photographs of the enemy lines.

All the while they were open to sniper fire and attack by fixed-wing planes.

The average flying life of a Royal Flying Corps pilot in the skies above the Arras region of Northern France was just 18 hours.

In April 1918, while up in an observation balloon, Geddes survived an attack by an enemy fighter plane when he and his companion were able to parachute to safety after their balloon was destroyed by fire.

Ironically, having survived attacks on his balloon, Geddes aged 26 was killed by a shell while on the ground.

As the most senior British kite balloon officer to be killed in action, Geddes was awarded the Military Cross and the Cross of the Legion of Honour.

Schomberg Byng, his friend and commanding officer, wrote a poignant letter to Alastair’s father telling him of his son’s death.

“We buried him very simply as I knew he would have liked,” he said.

With his mother Anna gravely ill, his father Patrick a famous polymath, planner and educationalist could not bring himself to tell her of Alastair’s death and continued to read her the last letters that Alastair had sent from the front.

A little over two months later, Anna died, unaware of her son’s demise.

Also on display will be maps from the conflict, one of which details the air raids that terrorised London.

Others record ship movement from Scapa Flow, off Orkney, and are signed by Earl Haig, a British senior officer at the time.

The RSGS visitor centre will be open from 10am until 4pm on Saturday and admission is free.