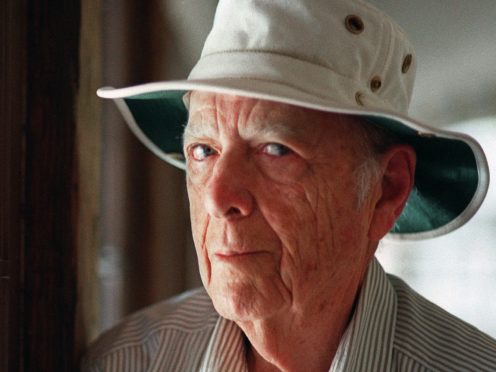

Herman Wouk, the Pulitzer Prize winning author of million-selling novels such as The Caine Mutiny and The Winds Of War, has died at the age of 103.

Wouk was just 10 days short of his 104th birthday and was working on a book until the end, said his literary agent Amy Rennert.

She said Wouk died in his sleep at his home in Palm Springs, California, where he settled after spending many years in Washington DC.

Among the last of the major writers to emerge after the Second World War and the first to bring Jewish stories to a general audience, he had a long, unpredictable career that included gag writing for radio star Fred Allen, historical fiction and a musical co-written with Jimmy Buffett.

He won the Pulitzer in 1952 for The Caine Mutiny, the classic navy drama that made the unstable Captain Queeg a symbol of authority gone mad.

A film adaptation, starring Humphrey Bogart, came out in 1954 and Wouk turned the courtroom scene into the play The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial.

Other highlights included Don’t Stop The Carnival, which Wouk and Buffett adapted into a musical, and his two-part epic The Winds Of War and War And Remembrance, both of which Wouk adapted for a 1983, Emmy Award-winning TV mini-series starring Robert Mitchum.

The Winds Of War received some of the highest ratings in TV history and Wouk’s involvement covered everything from the script to commercial sponsors.

Wouk was an outsider in the literary world. From Ernest Hemingway to James Joyce, major authors of the 20th century were assumed either anti-religious or at least highly sceptical, but Wouk was part of a smaller group that included CS Lewis who openly maintained traditional beliefs.

One of his most influential books was This Is My God, published in 1959 and an even-handed but firm defence of Judaism. For much of his life, he studied the Talmud daily and led a weekly Talmud class.

He gave speeches and sermons around the country and received several prizes, including a lifetime achievement award from the Jewish Book Council.

During his years in Washington, the Georgetown synagogue he attended was known unofficially as “Herman Wouk’s synagogue”.

Jews were present in most of Wouk’s books. Marjorie Morningstar, published in 1955, was one of the first million-selling novels about Jewish life, and two novels, The Hope and The Glory, were set in Israel.

Wouk had a mixed reputation among critics. He was not a poet or social rebel, and shared none of the demons that inspired the mad comedy of Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint. Even anthologies of Jewish literature tended to exclude him.

Gore Vidal praised him, faintly, by observing that Wouk’s “competence is most impressive and his professionalism awe-inspiring in a world of lazy writers and TV-stunned readers”.

But Wouk was widely appreciated for his historical detail, and he had an enviably large readership that stayed with him through several long novels. His friends and admirers ranged from Israeli prime ministers David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Rabin to Nobel laureates Saul Bellow and Elie Wiesel.

President Ronald Reagan, in a 1987 speech honouring 37 sailors killed on the USS Stark, quoted Wouk: “Heroes are not supermen; they are good men who embody — by the cast of destiny — the virtue of their whole people in a great hour.”

Wouk was well remembered in his latter years. In 1995, the Library of Congress marked his 80th birthday with a symposium on his career; historians David McCullough, Robert Caro, Daniel Boorstin and others were present.

In 2008, Wouk received the first Library of Congress Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Writing of Fiction. He published the novel The Lawgiver in his 90s and at 100 completed a memoir.

Wouk’s longevity inspired Stephen King to title one story Herman Wouk Is Still Alive.

The son of Russian Jews, Wouk was born in New York in 1915. The household was religious — his mother was a rabbi’s daughter — and devoted to books. His father would read to him from Sholem Aleichem, the great Yiddish writer.

A travelling salesman sold his family the entire works of Mark Twain, who became Wouk’s favourite writer, no matter how irreverent on matters of faith.

“I found it all very stimulating,” Wouk said in a rare interview in 2000. “His work is impregnated with references to the Bible. He may be scathing about it, but they’re there. He’s making jokes about religion, but the Jews are always making jokes about it.”

Wouk majored in comparative literature and philosophy at Columbia University and edited the college’s humour magazine. After graduation, he followed the path of so many bright New Yorkers in the 1930s and headed for California, where he worked for five years on Fred Allen’s radio show.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbour he enlisted in the navy and served as an officer in the Pacific. There, he received the writer’s most precious gift, free time, and wrote what became his first published novel, the radio satire Aurora Dawn.

“I was just having fun. It had never occurred to me write a novel,” he said.

In 1951, Wouk released his most celebrated novel, The Caine Mutiny. It sold slowly at first but eventually topped bestseller lists and won a Pulitzer.

But his next book looked into domestic matters. Wouk spoke often of his concern about assimilation and this story told of an aspiring Jewish actress whose real name was Marjorie Morgenstern. Her stage name provided the novel’s title, Marjorie Morningstar.

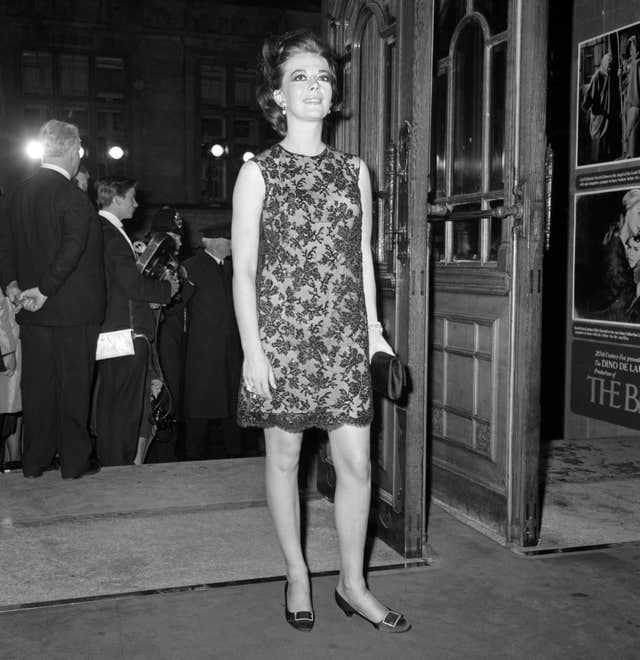

Like The Caine Mutiny, the novel sold millions and was made into a movie, starring Natalie Wood.

“I’m not out front as a figure, and that suits me,” he told the Associated Press. “I love the work and it’s the greatest possible privilege to say, ‘Here are these books that exist because I had to write them’. The fact that they were well received is just wonderful.”

In 1945, Wouk married Betty Sarah Brown, who also served as his agent. They had three sons — Nathaniel, Joseph and their eldest, Abraham, who drowned in 1951.