A small pass in the Swiss Alps may seem like an unusual location to start a metaphor charting Scotland’s potential ascent to cricketing supremacy.

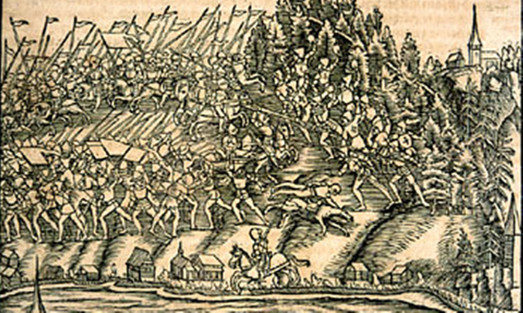

Yet, the Battle of Morgarten, which took place in 1315, provides the perfect analogy if only because, as with much of late medieval history, it is so mired in loose facts that they can easily be rearranged to suit any argument.

The two sides in the fight were the Holy Roman Empire, under Duke Leopold I, and the burgeoning Swiss Confederation.

With a hubris only German’s can muster, professional knights, armed to the teeth, believed they would have little difficulty in crushing the Swiss upstarts.

One contemporary travelling with Leopold’s army remarked: “The men of this army came together with one purpose: to utterly subdue and humiliate those peasants who were surrounded with mountains as with walls.”

Such pride inevitably comes before the fall.

The troops of the Holy Roman Empire were crushed pretty literally by the smaller, amateur Swiss forces, who trapped them in the Morgarten Pass before pelting them from above with an avalanche of boulders.

Around 1500 of Leopold’s men were killed and the foundations of the modern-day state of Switzerland were born.

As Scotland prepare to face England this evening (22:00 GMT), they would be wise to look to the example of Morgarten (although I’m under no illusion that they will).

In cricketing terms, the Holy Roman Empire of 1315 was certainly a Test-playing nation.

But it was also one much like the England team seems to be of disparate parts, and battered from all sides.

Individually the principalities of the Holy Roman Empire were strong, but they struggled to pull together for victory, as at Morgarten.

Indeed, Leopold I himself was no stranger to the kind of intrigue and factionalism found in the England dressing room in recent years. He would have been all too familiar with the type of purges that have seen the likes of Alistair Cook and, dare I say it, Kevin Pietersen, left in exile.

Scotland, on the other hand, has no such issue. Still seeking their first World Cup victory, the Saltires enter tonight’s match as the underdogs but underdogs more than capable of rolling boulders off a hill.

On paper the England squad is stronger individually, but they are not playing as a coherent team. Scotland is very much the opposite.

Their strong showing against New Zealand, comparatively speaking, gives them a good grounding as they come to face their neighbors south of the border.

And if they continue to club together and show a resilience the Swiss would be proud of, they can do very well tonight.

Indeed, as Morgarten proved to be the founding of the modern Swiss state, so to could victory tonight open a new chapter in Scottish cricket.

England Eoin Morgan and Peter Moores in particular don’t believe their side have a problem and are as confident as Leopold I of victory.

They are in absolute denial about the manner of their recent defeats and are refusing to admit that, mentally at least, the squad does not seem up to the challenge.

But, as the Holy Roman Empire learned at Morgarten, there’s a great deal more to winning than being the stronger side on paper.